Russo-Japanese War

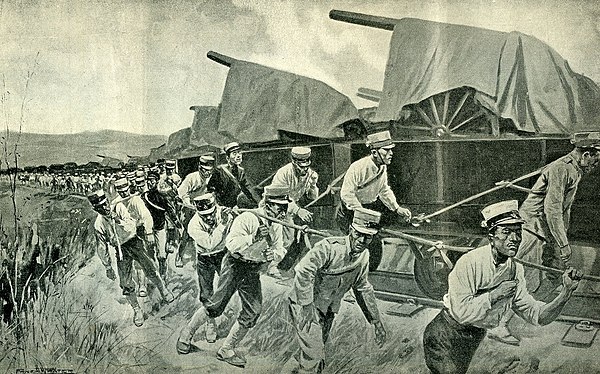

The Russo-Japanese War was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1905 over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major theatres of military operations were located in Liaodong Peninsula and Mukden in Southern Manchuria, and the Yellow Sea and the Sea of Japan. Russia sought a warm-water port on the Pacific Ocean both for its navy and for maritime trade. Vladivostok remained ice-free and operational only during the summer; Port Arthur, a naval base in Liaodong Province leased to Russia by the Qing dynasty of China from 1897, was operational year round. Russia had pursued an expansionist policy east of the Urals, in Siberia and the Far East, since the reign of Ivan the Terrible in the 16th century. Since the end of the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895, Japan had feared Russian encroachment would interfere with its plans to establish a sphere of influence in Korea and Manchuria.

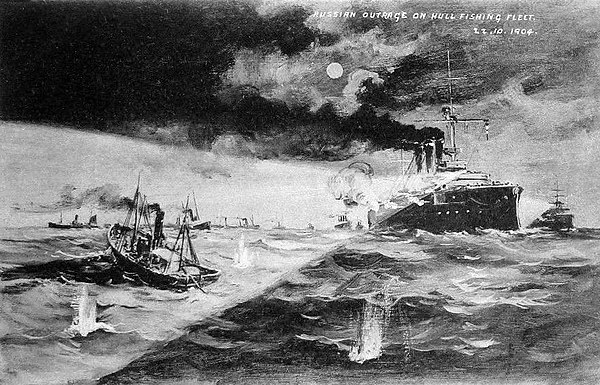

Seeing Russia as a rival, Japan offered to recognize Russian dominance in Manchuria in exchange for recognition of the Korean Empire as being within the Japanese sphere of influence. Russia refused and demanded the establishment of a neutral buffer zone between Russia and Japan in Korea, north of the 39th parallel. The Imperial Japanese Government perceived this as obstructing their plans for expansion into mainland Asia and chose to go to war. After negotiations broke down in 1904, the Imperial Japanese Navy opened hostilities in a surprise attack on the Russian Eastern Fleet at Port Arthur, China on 9 February 1904.

Although Russia suffered a number of defeats, Emperor Nicholas II remained convinced that Russia could still win if it fought on; he chose to remain engaged in the war and await the outcomes of key naval battles. As hope of victory dissipated, he continued the war to preserve the dignity of Russia by averting a "humiliating peace." Russia ignored Japan's willingness early on to agree to an armistice and rejected the idea of bringing the dispute to the Permanent Court of Arbitration at the Hague. The war was eventually concluded with the Treaty of Portsmouth (5 September 1905), mediated by United States. The complete victory of the Japanese military surprised international observers and transformed the balance of power in both East Asia and Europe, resulting in Japan's emergence as a great power and a decline in the Russian Empire's prestige and influence in Europe. Russia's incurrence of substantial casualties and losses for a cause that resulted in humiliating defeat contributed to a growing domestic unrest which culminated in the 1905 Russian Revolution, and severely damaged the prestige of the Russian autocracy.