Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the overthrowing of the monarchy and the new republican government's failure to maintain stability, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. It resulted in the formation of the RSFSR and later the Soviet Union in most of its territory. Its finale marked the end of the Russian Revolution, which was one of the key events of the 20th century.

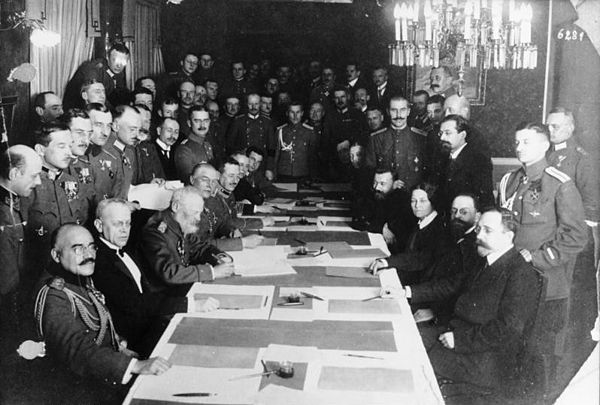

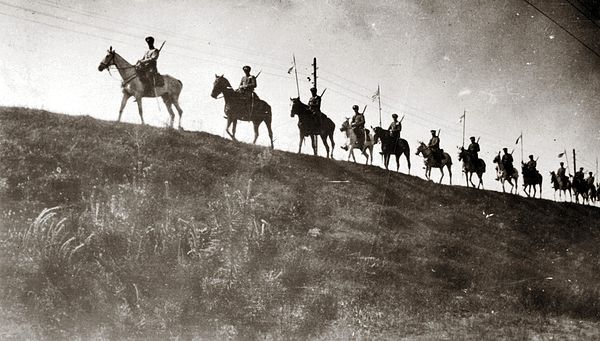

The Russian monarchy had been overthrown by the 1917 February Revolution, and Russia was in a state of political flux. A tense summer culminated in the Bolshevik-led October Revolution, overthrowing the Provisional Government of the Russian Republic. Bolshevik rule was not universally accepted, and the country descended into civil war. The two largest combatants were the Red Army, fighting for the Bolshevik form of socialism led by Vladimir Lenin, and the loosely allied forces known as the White Army, which included diverse interests favouring political monarchism, capitalism and social democracy, each with democratic and anti-democratic variants. In addition, rival militant socialists, notably the Ukrainian anarchists of the Makhnovshchina and Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, as well as non-ideological green armies, opposed the Reds, the Whites and foreign interventionists. Thirteen foreign nations intervened against the Red Army, notably the former Allied military forces from the World War with the goal of re-establishing the Eastern Front. Three foreign nations of the Central Powers also intervened, rivaling the Allied intervention with the main goal of retaining the territory they had received in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

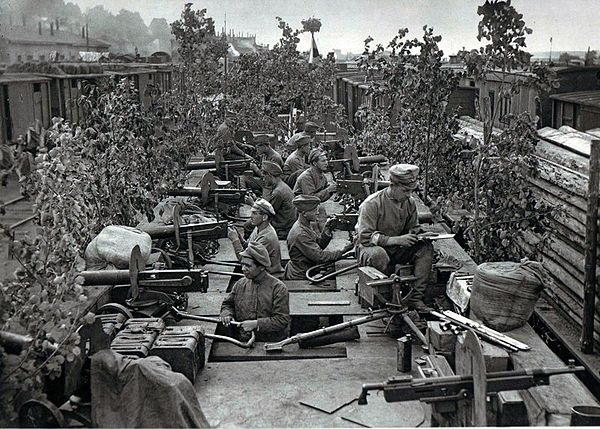

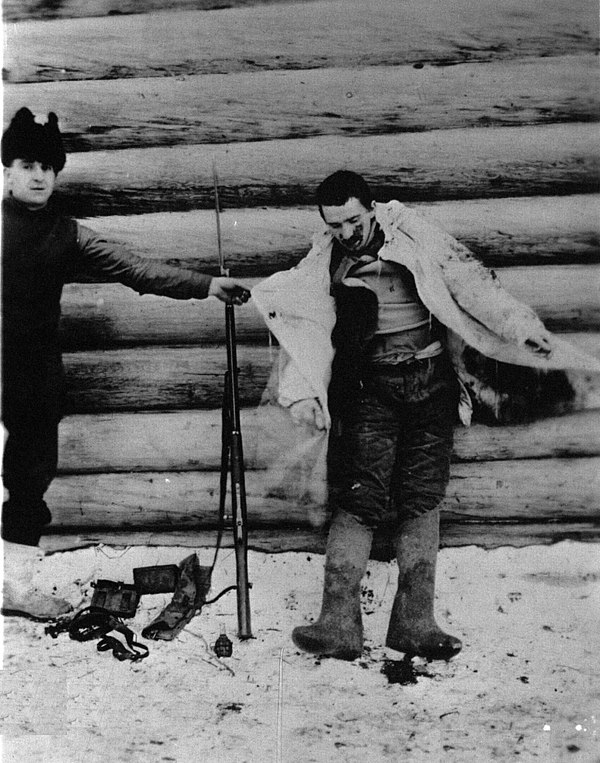

Most of the fighting in the first period was sporadic, involved only small groups and had a fluid and rapidly-shifting strategic situation. Among the antagonists were the Czechoslovak Legion, the Poles of the 4th and 5th Rifle Divisions and the pro-Bolshevik Red Latvian riflemen.

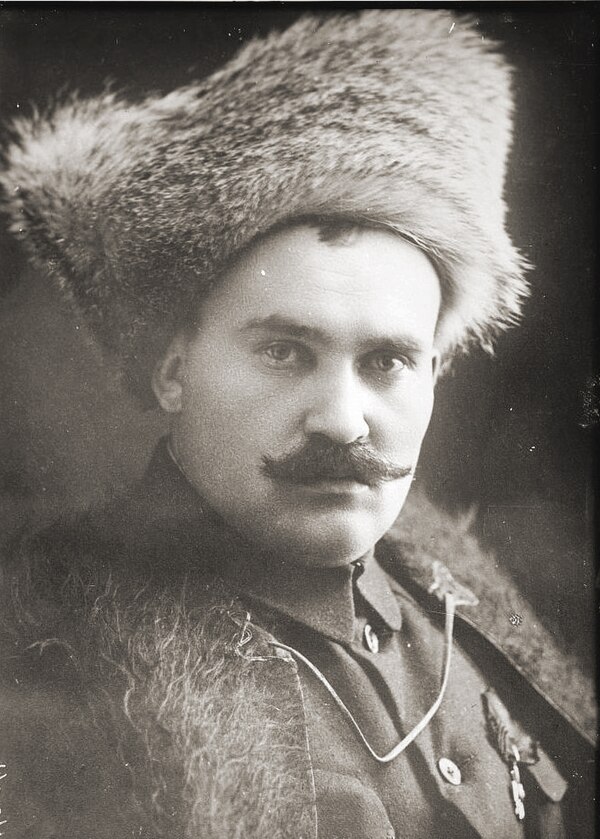

The second period of the war lasted from January to November 1919. At first the White armies' advances from the south (under Denikin), the east (under Kolchak) and the northwest (under Yudenich) were successful, forcing the Red Army and its allies back on all three fronts. In July 1919 the Red Army suffered another reverse after a mass defection of units in the Crimea to the anarchist Insurgent Army under Nestor Makhno, enabling anarchist forces to consolidate power in Ukraine. Leon Trotsky soon reformed the Red Army, concluding the first of two military alliances with the anarchists. In June the Red Army first checked Kolchak's advance. After a series of engagements, assisted by an Insurgent Army offensive against White supply lines, the Red Army defeated Denikin's and Yudenich's armies in October and November.

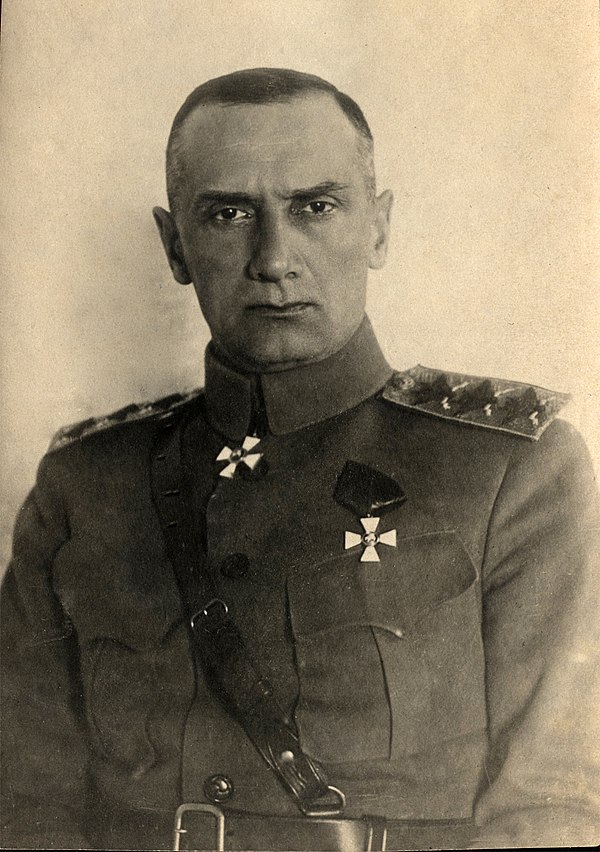

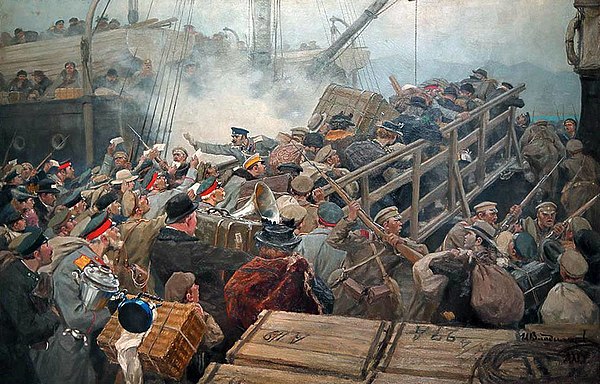

The third period of the war was the extended siege of the last White forces in the Crimea. General Wrangel had gathered the remnants of Denikin's armies, occupying much of the Crimea. An attempted invasion of southern Ukraine was rebuffed by the Insurgent Army under Makhno's command. Pursued into Crimea by Makhno's troops, Wrangel went over to the defensive in the Crimea. After an abortive move north against the Red Army, Wrangel's troops were forced south by Red Army and Insurgent Army forces; Wrangel and the remains of his army were evacuated to Constantinople in November 1920.