Suleiman the Magnificent

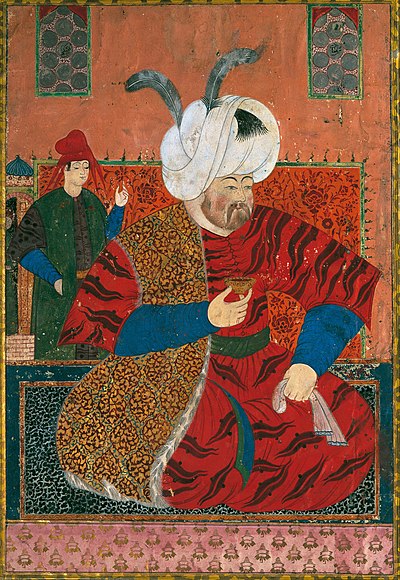

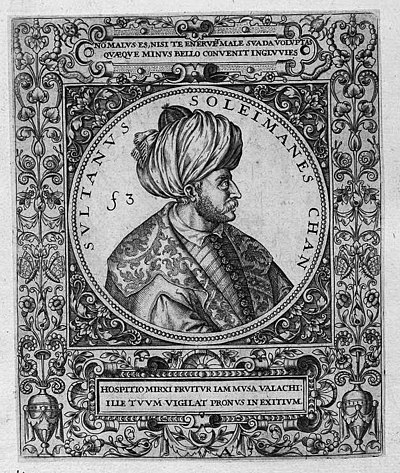

Suleiman I, commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent, was the tenth and longest-reigning Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1520 until his death in 1566.

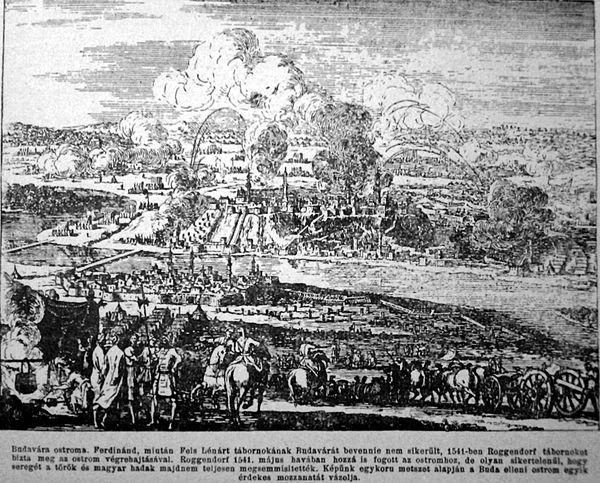

Suleiman became a prominent monarch of 16th-century Europe, presiding over the apex of the Ottoman Empire's economic, military and political power. Suleiman began his reign with campaigns against the Christian powers in central Europe and the Mediterranean. Belgrade fell to him in 1521 and the island of Rhodes in 1522–23. At Mohács, in August 1526, Suleiman broke the military strength of Hungary. Suleiman personally led Ottoman armies in conquering the Christian strongholds of Belgrade and Rhodes as well as most of Hungary before his conquests were checked at the siege of Vienna in 1529. He annexed much of the Middle East in his conflict with the Safavids and large areas of North Africa as far west as Algeria. Under his rule, the Ottoman fleet dominated the seas from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea and through the Persian Gulf.

At the helm of an expanding empire, Suleiman personally instituted major judicial changes relating to society, education, taxation and criminal law. His reforms, carried out in conjunction with the empire's chief judicial official Ebussuud Efendi, harmonized the relationship between the two forms of Ottoman law: sultanic (Kanun) and religious (Sharia).He was a distinguished poet and goldsmith; he also became a great patron of culture, overseeing the "Golden" age of the Ottoman Empire in its artistic, literary and architectural development.