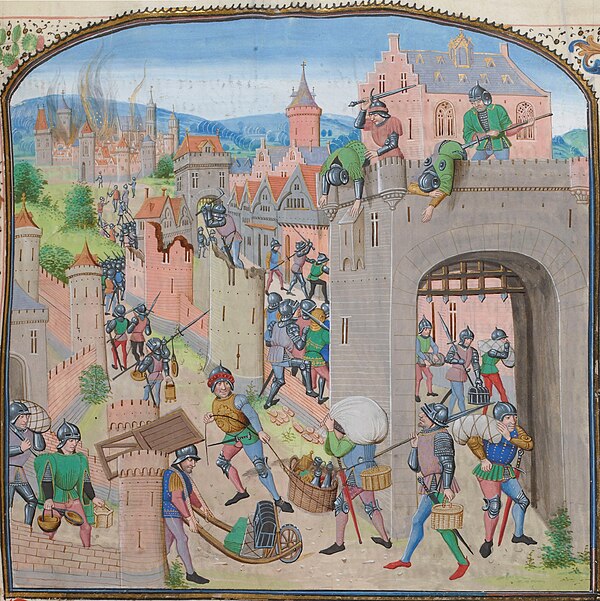

At the beginning of February, King Philip VI appointed a new Admiral of France, one Nicholas Béhuchet, who had previously served as a treasury official and now was instructed to wage economic warfare against England. On 24 March 1338 he began his campaign, leading a large fleet of small coastal ships across the Channel from Calais and into the Solent where they landed and burnt the vitally important port-town of Portsmouth. The town was unwalled and undefended and the French were not suspected as they sailed towards the town with English flags flying. The result was a disaster for Edward, as the town's shipping and supplies were looted, the houses, stores, and docks burnt down, and those of the population unable to flee were killed or taken off as slaves. No English ships were available to contest their passage from Portsmouth and none of the militias intended to form in such an instance made an appearance.

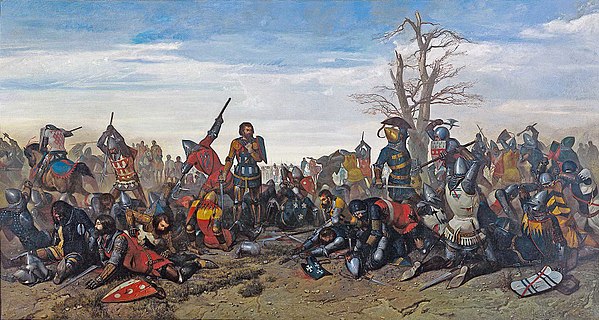

The campaign at sea resumed in September 1338, when a large French and Italian fleet descended on the Channel Islands once again under Robert VIII Bertrand de Bricquebec, Marshal of France. The island of Sark, which had suffered a serious raid the year before, fell without a fight and Guernsey was captured after a brief campaign. The island was largely undefended, as most of the Channel Islands garrison was in Jersey to prevent another raid there, and the few that were sent to Guernsey and Sark were captured at sea. On Guernsey, the forts of Castle Cornet and Vale Castle were the only points to hold out. Neither fort lasted very long as both were undermanned and unprovisioned. The garrisons were put to death. A brief naval battle was fought between Channel Islanders in coastal and fishing vessels and Italian galleys, but despite two of the Italian ships being sunk the Islanders were defeated with heavy casualties.

The next target for Béhuchet and his lieutenant Hugh Quiéret were the supply lines between England and Flanders, and they gathered 48 large galleys at Harfleur and Dieppe. This fleet then attacked an English squadron at Walcheren on 23 September. The English vessels were unloading cargo and were surprised and overwhelmed after bitter fighting, resulting in the capture of five large and powerful English cogs, including Edward III's flagships the Cog Edward and the Christopher. The captured crews were executed and the ships added to the French fleet.

A few days later on 5 October, this force conducted its most damaging raid of all, landing several thousand French, Norman, Italian and Castilian sailors close to the major port of Southampton and assaulting it from both land and sea. The town's walls were old and crumbling and direct orders to repair it had been ignored. Most of the town's militia and citizens fled in panic into the countryside, with only the castle's garrison holding out until a force of Italians breached the defenses and the town fell. The scenes of Portsmouth were repeated as the entire town was razed to the ground, thousands of pounds worth of goods and shipping took back to France, and captives massacred or taken as slaves.

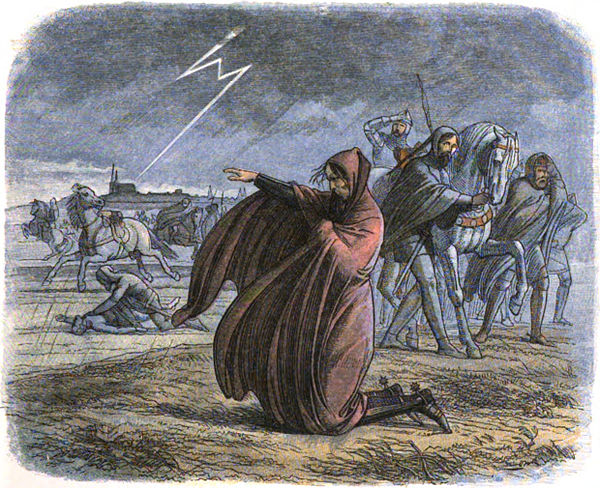

An early winter forced a pause in the Channel warfare, and 1339 saw a vastly different situation, as English towns had taken the initiative over the winter and prepared organised militias to drive off raiders more interested in plunder than set-piece battles. An English fleet had also been constituted over the winter and this was used in an effort to gain revenge on the French by attacking coastal shipping.

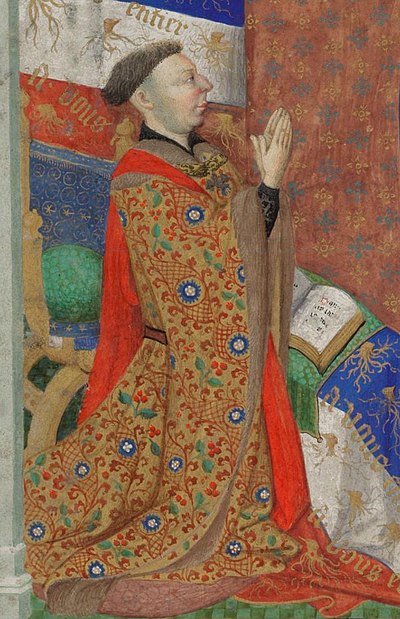

Morley took his fleet to the French coast, burning the towns of Ault and Le Tréport and foraging inland, ravaging several villages and provoking a panic to mirror that at Southampton the year before. He also surprised and destroyed a French fleet in Boulogne harbor. English and Flemish merchants rapidly fitted out raiding ships and soon coastal villages and shipping along the North and even the west coasts of France were under attack. The Flemish navy too was active, sending their fleet against the important port of Dieppe in September and burning it to the ground. These successes did much to rebuild morale in England and the Low Countries as well as repair England's battered trade. It did not however have anything like the financial impact of the earlier French raids as France's continental economy could survive depredations from the sea much better than the maritime English.