Second Crusade

The Second Crusade was started in response to the fall of the County of Edessa in 1144 to the forces of Zengi. The county had been founded during the First Crusade by King Baldwin I of Jerusalem in 1098.

The Second Crusade was started in response to the fall of the County of Edessa in 1144 to the forces of Zengi. The county had been founded during the First Crusade by King Baldwin I of Jerusalem in 1098.

There were three crusader states established in the east: the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Principality of Antioch and the County of Edessa. A fourth, the County of Tripoli, was established in 1109. Edessa was the most northerly of these, and also the weakest and least populated; as such, it was subject to frequent attacks from the surrounding Muslim states ruled by the Ortoqids, Danishmends and Seljuq Turks. Edessa fell in 1144. The news of the fall of Edessa was brought back to Europe first by pilgrims early in 1145, and then by embassies from Antioch, Jerusalem and Armenia. Bishop Hugh of Jabala reported the news to Pope Eugene III, who issued the bull Quantum praedecessores on 1 December of that Year, calling for a second crusade.

The siege of Edessa in October–November 1146 marked the permanent end of the rule of the Frankish Counts of Edessa in the city on the eve of the Second Crusade. It was the second siege the city had suffered in as many years, the first siege of Edessa having ended in December 1144. In 1146, Joscelyn II of Edessa and Baldwin of Marash recaptured the city by stealth but could not take or even properly besiege the citadel. After a brief counter-siege, Zangid governor Nūr al-Dīn took the city. The population was massacred and the walls razed. This victory was pivotal in the rise of Nūr al-Dīn and the decline of the Christian city of Edessa.

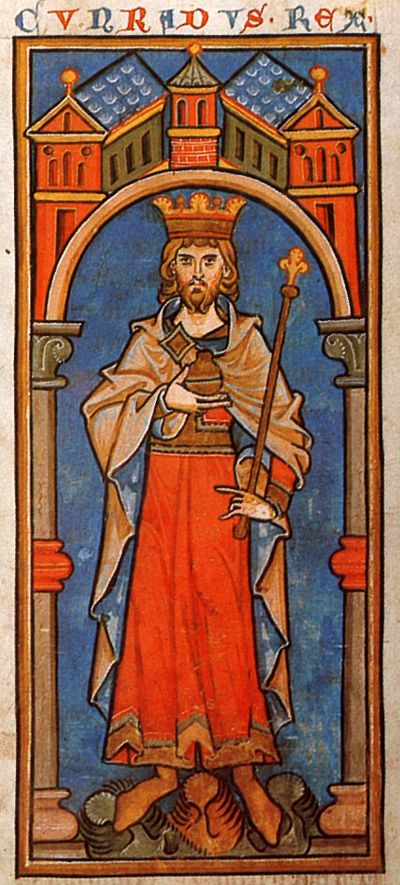

On 16 February 1147, the French crusaders met at Étampes to discuss their route. The Germans had already decided to travel overland through Hungary; they regarded the sea route as politically impractical because Roger II of Sicily was an enemy of Conrad. Many of the French nobles distrusted the land route, which would take them through the Byzantine Empire, the reputation of which still suffered from the accounts of the First Crusaders. Nevertheless, the French decided to follow Conrad, and to set out on 15 June.

When the Second Crusade was called, many south Germans volunteered to crusade in the Holy Land. The north German Saxons were reluctant. They told St Bernard of their desire to campaign against pagan Slavs at an Imperial Diet meeting in Frankfurt on 13 March 1147. Approving of the Saxons' plan, Eugenius issued a papal bull known as the Divina dispensatione on 13 April. This bull stated that there was to be no difference between the spiritual rewards of the different crusaders. Those who volunteered to crusade against the pagan Slavs were primarily Danes, Saxons and Poles, although there were also some Bohemians. The Wends are made up of the Slavic tribes of Abrotrites, Rani, Liutizians, Wagarians, and Pomeranians who lived east of the River Elbe in present-day northeast Germany and Poland.

In the spring of 1147, the Pope authorized the expansion of the crusade into the Iberian peninsula, in the context of the Reconquista. He also authorized Alfonso VII of León and Castile to equate his campaigns against the Moors with the rest of the Second Crusade.

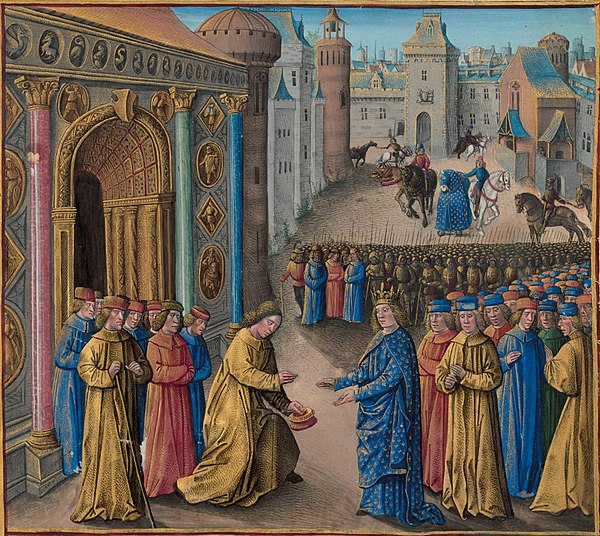

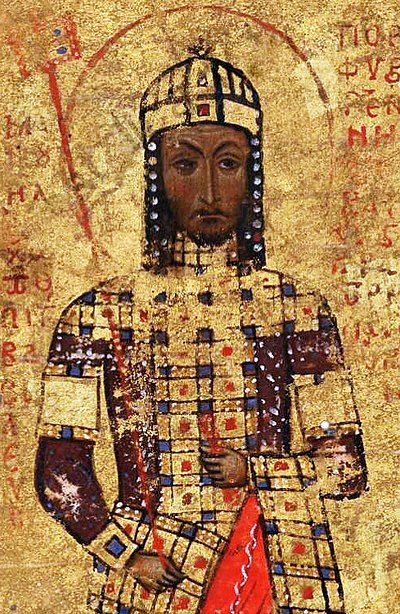

The German crusaders, accompanied by the papal legate and cardinal Theodwin, intended to meet the French in Constantinople. Conrad's enemy Géza II of Hungary allowed them to pass through unharmed. When the German army of 20,000 men arrived in Byzantine territory, Emperor Manuel I Komnenos feared they were going to attack him, and had Byzantine troops posted to ensure against trouble.

In May 1147, the first contingents of crusaders left from Dartmouth in England for the Holy Land. Bad weather forced the ships to stop on the Portuguese coast, at the northern city of Porto on 16 June 1147. There they were convinced to meet with King Afonso I of Portugal. The crusaders agreed to help the King attack Lisbon, with a solemn agreement that offered to them the pillage of the city's goods and the ransom money for expected prisoners.

The siege of Lisbon, from 1 July to 25 October 1147, was the military action that brought the city of Lisbon under definitive Portuguese control and expelled its Moorish overlords. The siege of Lisbon was one of the few Christian victories of the Second Crusade. It is seen as a pivotal battle of the wider Reconquista. On October 1147, after a four month siege, the Moorish rulers agreed to surrender, primarily due to hunger within the city. Most of the crusaders settled in the newly captured city, but some of them set sail and continued to the Holy Land. Some of them, who had departed earlier, helped capture Santarém earlier in the same Year. Later they also helped to conquer Sintra, Almada, Palmela and Setúbal, and they were allowed to stay in the conquered lands, where they settled down and had offspring.

The Battle of Constantinople in 1147 was a large-scale clash between the forces of the Byzantine Empire and the German crusaders of the Second Crusade, led by Conrad III of Germany, fought on the outskirts of the Byzantine capital, Constantinople. The Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos was deeply concerned by the presence of a large and unruly army in the immediate vicinity of his capital and of the unfriendly attitude of its leaders. A similarly sized French crusader army was also approaching Constantinople, and the possibility of the two armies combining at the city was viewed with great alarm by Manuel. Following earlier armed clashes with the crusaders, and perceived insults from Conrad, Manuel arrayed some of his forces outside the walls of Constantinople. A part of the German army then attacked and was heavily defeated. Following this defeat the crusaders agreed to be quickly ferried across the Bosporus to Asia Minor.

In Asia Minor, Conrad decided not to wait for the French, but marched towards Iconium, capital of the Sultanate of Rûm. Conrad split his army into two divisions. Conrad took the knights and the best troops with himself to march overland while sending the camp followers with Otto of Freising to follow the coastal road. Once beyond effective Byzantine control, the German army came under constant harassing attacks from the Turks, who excelled at such tactics. The poorer, and less well-supplied, infantry of the crusader army were the most vulnerable to hit-and-run horse archer attack and began to take casualties and lose men to capture. The area through which the crusaders were marching was largely barren and parched; therefore the army could not augment its supplies and was troubled by thirst. When the Germans were about three days march beyond Dorylaeum, the nobility requested that the army turn back and regroup. As the crusaders began their retreat, on 25 October, the Turkish attacks intensified and order broke down, the retreat then becoming a rout with the Crusaders taking heavy casualties.

The force led by Otto ran out of food while crossing inhospitable countryside and was ambushed by the Seljuq Turks near Laodicea on 16 November 1147. The majority of Otto's force were either killed in battle or captured and sold into slavery.

The French army Laodicea on the Lycus early in January 1148, just after Otto of Freising's army had been destroyed in the same area. Resuming the march, the vanguard under Amadeus of Savoy became separated from the rest of the army at Mount Cadmus, where Louis's troops suffered heavy losses from the Turks (6 January 1148). The Turks did not bother to attack further and the French marched on to Adalia, continually harassed from afar by the Turks, who had also burned the land to prevent the French from replenishing their food, both for themselves and their horses. Louis no longer wanted to continue by land, and it was decided to gather a fleet at Adalia and to sail for Antioch. After being delayed for a month by storms, most of the promised ships did not arrive at all. Louis and his associates claimed the ships for themselves, while the rest of the army had to resume the long march to Antioch. The army was almost entirely destroyed, either by the Turks or by sickness.

A council to decide on the best target for the crusaders took place on 24 June 1148, when the Haute Cour of Jerusalem met with the recently arrived crusaders from Europe at Palmarea, near Acre, a major city of the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. This was the most spectacular meeting of the Court in its existence. In the end, the decision was made to attack the city of Damascus, a former ally of the Kingdom of Jerusalem that had shifted its allegiance to that of the Zengids, and attacked the Kingdom's allied city of Bosra in 1147.

The crusaders decided to attack Damascus from the west, where orchards of Ghouta would provide them with a constant food supply. Having arrived outside the walls of the city, they immediately put it to siege, using wood from the orchards. On 27 July, the crusaders decided to move to the plain on the eastern side of the city, which was less heavily fortified but had much less food and water. Afterwards, the local crusader lords refused to carry on with the siege, and the three kings had no choice but to abandon the city. The entire crusader army retreated back to Jerusalem by 28 July.

In June 1149, Nur ad-Din invaded Antioch and besieged the fortress of Inab, with aid from Unur of Damascus and a force of Turcomans. Nur ad-Din had about 6,000 troops, mostly cavalry, at his disposal. Raymond and his Christian neighbor, Count Joscelin II of Edessa, had been enemies since Raymond had refused to send an army to relieve besieged Edessa in 1146. Joscelin even made a treaty of alliance with Nur ad-Din against Raymond. For their part, Raymond II of Tripoli and the regent Melisende of Jerusalem refused to aid the Prince of Antioch. Feeling confident because he had twice defeated Nur ad-Din previously, Prince Raymond struck out on his own with an army of 400 knights and 1,000 foot soldiers.

Prince Raymond allied himself with Ali ibn-Wafa, a leader of the Assassins and an enemy of Nur ad-Din. Before he had collected all his available forces, Raymond and his ally mounted a relief expedition. Amazed at the weakness of Prince Raymond's army, Nur ad-Din at first suspected that it was only an advance guard and that the main Frankish army must be lurking nearby. Upon the approach of the combined force, Nur ad-Din raised the siege of Inab and withdrew. Rather than staying close to the stronghold, Raymond and ibn-Wafa camped with their forces in open country. After Nur ad-Din's scouts noted that the allies camped in an exposed location and did not receive reinforcements, the atabeg swiftly surrounded the enemy camp during the night.

On 29 June, Nur ad-Din attacked and destroyed the army of Antioch. Presented with an opportunity to escape, the Prince of Antioch refused to abandon his soldiers. Raymond was a man of "immense stature" and fought back, "cutting down all who came near him". Nevertheless, both Raymond and ibn-Wafa were killed, along with Reynald of Marash. A few Franks escaped the disaster. Much of the territory of Antioch was now open to Nur ad-Din, the most important of which was a route to the Mediterranean. Nur ad-Din rode out to the coast and bathed in the sea as a symbol of his conquest.

After his victory, Nur ad-Din went on to capture the fortresses of Artah, Harim, and ‘Imm, which defended the approach to Antioch itself. After the victory at Inab, Nur ad-Din became a hero throughout the Islamic world. His goal became the destruction of the Crusader states, and the strengthening of Islam through jihad.

Each of the Christian forces felt betrayed by the other. After quitting Ascalon, Conrad returned to Constantinople to further his alliance with Manuel. Louis remained behind in Jerusalem until 1149. Back in Europe, Bernard of Clairvaux was humiliated by the defeat. Bernard considered it his duty to send an apology to the Pope and it is inserted in the second part of his Book of Consideration. Relations between the Eastern Roman Empire and the French were badly damaged by the Crusade. Louis and other French leaders openly accused the Emperor Manuel I of colluding with Turkish attacks on them during the march across Asia Minor. Baldwin III finally seized Ascalon in 1153, which brought Egypt into the sphere of conflict. In 1187, Saladin captures Jerusalem. His forces then spread north to capture all but the capital cities of the Crusader States, precipitating the Third Crusade.

Explore the rich history of the American Revolution through this captivating painting of the Continental Army. Perfect for history enthusiasts and art collectors, this piece brings to life the bravery and struggles of early American soldiers.

Burgundian Abbot

Count of Edessa

Emir of Mosul

Queen Consort of France

King of France

Byzantine Emperor

Holy Roman Emperor

King of Jerusalem

Bishop of Freising

Emir of Aleppo

Catholic Pope

Emir of Sham

Atabeg of Mosul

Prince of Antioch