Edo Period

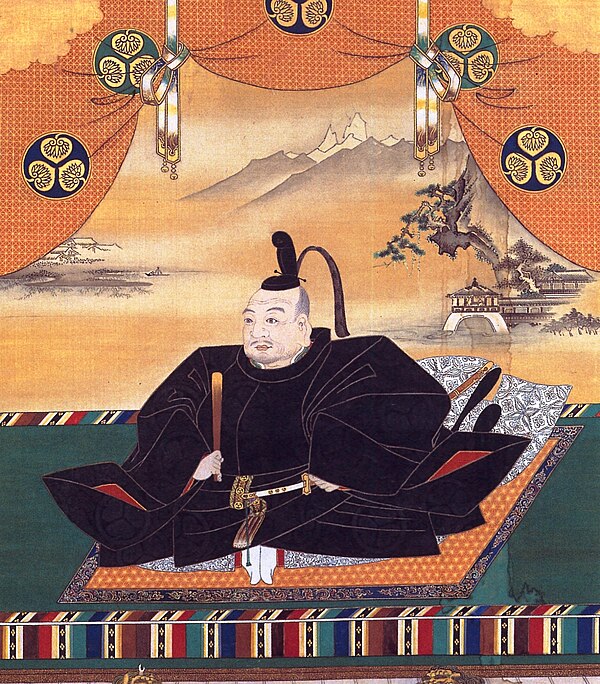

The Edo period, also known as the Tokugawa period, lasted from 1603 to 1868. This era was marked by nearly 260 years of peace and stability under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate, which was established by Tokugawa Ieyasu after his victory at the Battle of Sekigahara.

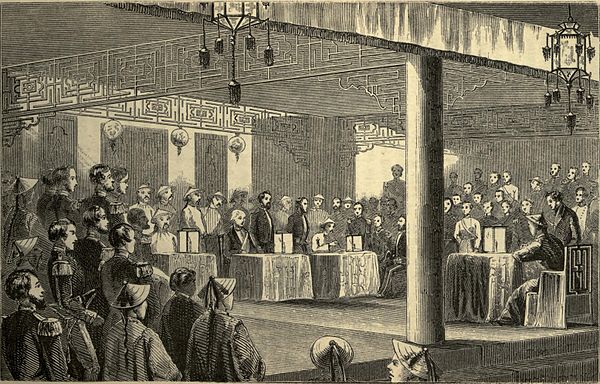

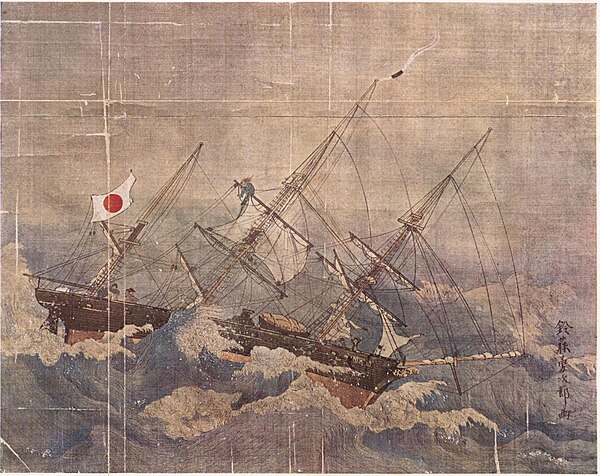

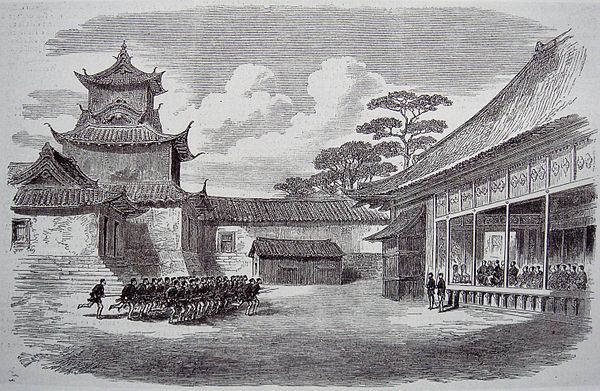

During the Edo period, Japan implemented a strict social order based on Confucian principles, dividing society into four main classes: samurai, peasants, artisans, and merchants, with the samurai class at the top. This period was characterized by the policy of sakoku, or national isolation, which severely limited foreign influence and trade; only the Dutch and Chinese were allowed restricted trade through the port of Nagasaki.

Economically, the period saw significant growth and urbanization. The development of a vibrant merchant class and the rise of a consumer culture led to the flourishing of arts and culture, including kabuki theater, ukiyo-e woodblock prints, and the tea ceremony.

Intellectually, the Edo period was a time of learning and education, spreading literacy and scholarly pursuits among the samurai and common people alike. Native learning, or Kokugaku, emerged to promote Japanese thought and Shinto religion, often in reaction against Confucian and Buddhist influences.

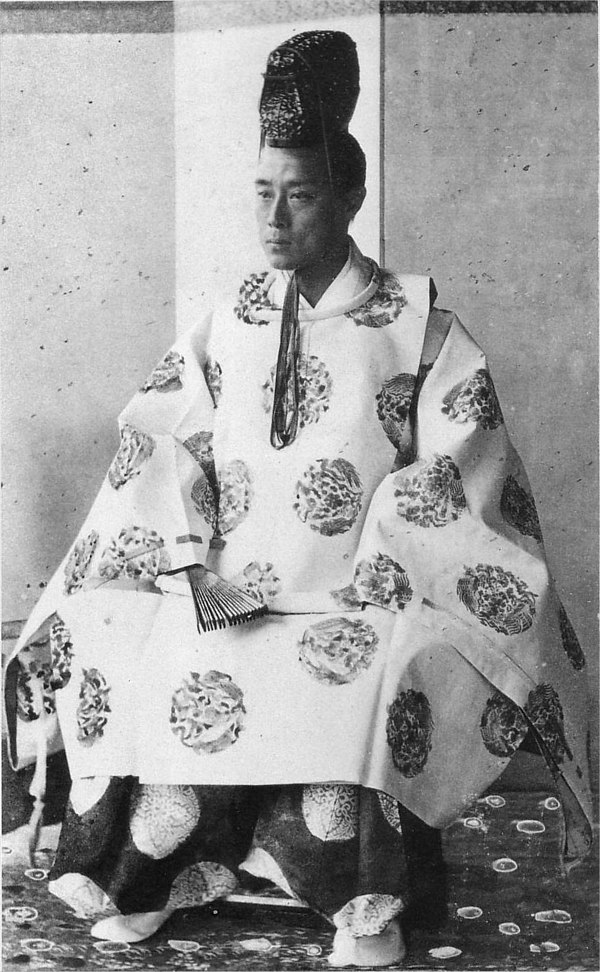

The period came to an end when the Tokugawa shogunate was overthrown in the Meiji Restoration of 1868, which restored imperial rule and set Japan on a path of rapid modernization and industrialization.