History of Taiwan

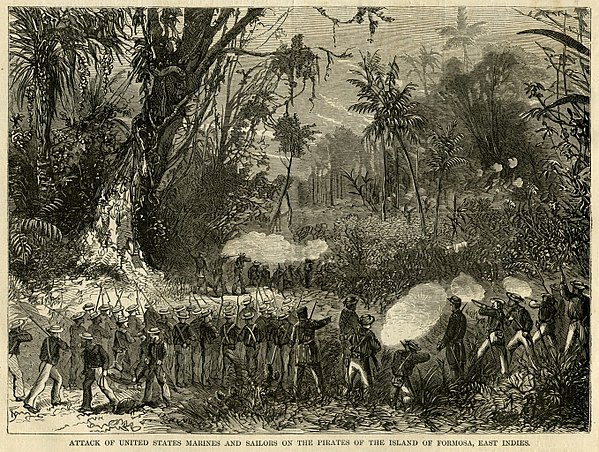

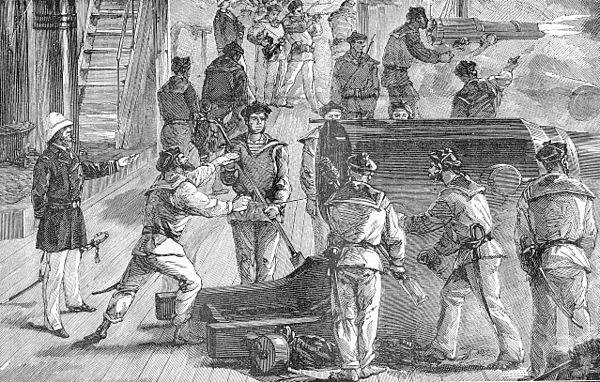

Taiwan's history spans tens of thousands of years,[1] beginning with the earliest evidence of human habitation and the emergence of an agricultural culture around 3000 BCE, attributed to the ancestors of today's Taiwanese indigenous peoples.[2] The island saw contact from the Han Chinese in the late 13th century and subsequent settlements in the 17th century. European exploration led to the naming of the island as Formosa by the Portuguese, with the Dutch colonizing the south and the Spanish the north. The European presence was followed by an influx of Hoklo and Hakka Chinese immigrants. By 1662, Koxinga defeated the Dutch, establishing a stronghold that was later annexed by the Qing dynasty in 1683. Under Qing rule, Taiwan's population surged and became predominantly Han Chinese due to migrations from mainland China.

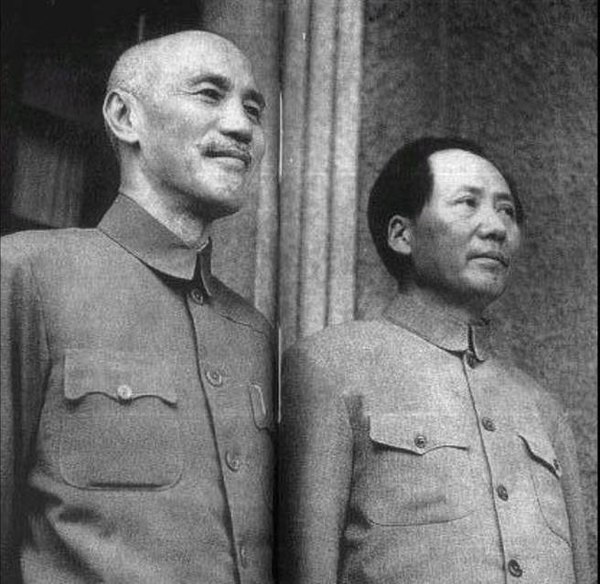

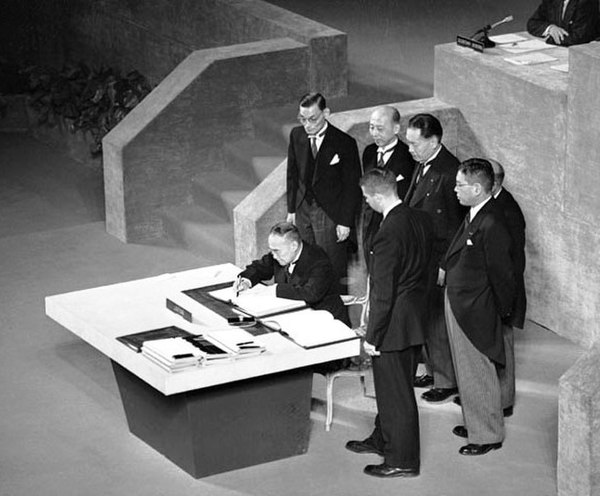

In 1895, after the Qing lost the First Sino-Japanese War, Taiwan and Penghu were ceded to Japan. Under Japanese rule, Taiwan underwent industrial growth, becoming a significant exporter of rice and sugar. It also served as a strategic base during the Second Sino-Japanese War, facilitating invasions of China and other regions during World War II. Post-war, in 1945, Taiwan came under the control of the Republic of China (ROC) led by the Kuomintang (KMT) following the cessation of World War II hostilities. However, the legitimacy and nature of ROC's control, including the transfer of sovereignty, remain subjects of debate.[3]

By 1949, the ROC, having lost mainland China in the Chinese Civil War, retreated to Taiwan, where Chiang Kai-shek declared martial law and the KMT established a single-party state. This lasted for four decades until democratic reforms took place in the 1980s, culminating in the first direct presidential election in 1996. During the post-war years, Taiwan witnessed remarkable industrialization and economic progress, famously termed the "Taiwan Miracle", positioning it as one of the "Four Asian Tigers".