Background

The Crusader States, including Antioch, were frequently in conflict with Muslim states such as Aleppo and Mosul. The death of Ridwan of Aleppo in 1113 briefly ushered in peace, yet Roger of Salerno, Antioch's regent, Baldwin II of Edessa, and Pons of Tripoli, did not consolidate against Aleppo. In 1115, Roger repelled a Seljuk invasion at the Battle of Sarmin.

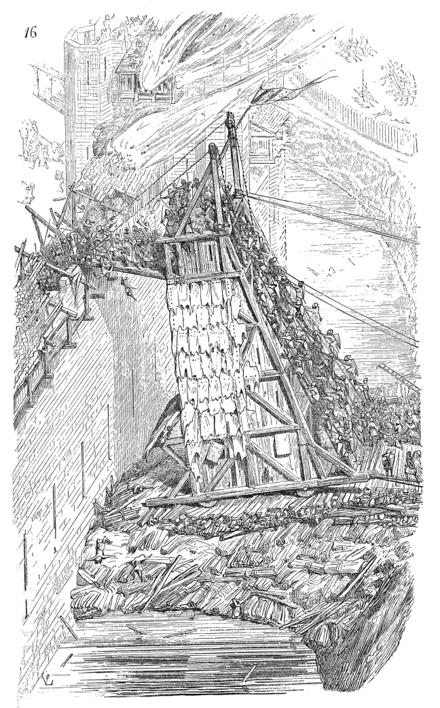

By 1117, Aleppo was under Ilghazi of the Artuqid dynasty. Following Roger's capture of Azaz in 1118, making Aleppo vulnerable, Ilghazi invaded Antioch in 1119. Despite advice from Bernard of Valence, the Latin Patriarch of Antioch, to utilize the fortified position of Artah and call for reinforcements, Roger opted for a more aggressive stance at the Sarmada pass. During Ilghazi's siege of al-Atharib, a Crusader sortie led by Robert of Vieux-Pont was lured into an ambush by Ilghazi's feigned retreat, demonstrating the tactical challenges faced by the Crusaders in their confrontations with Muslim forces.

Battle

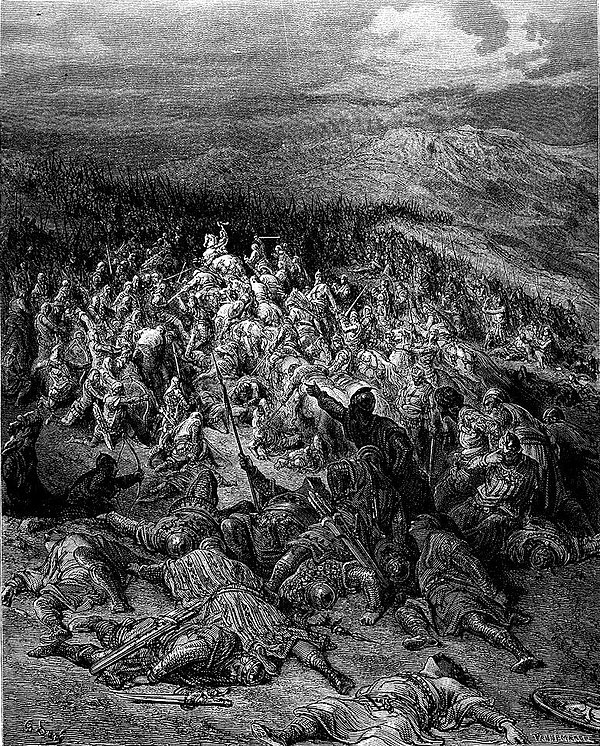

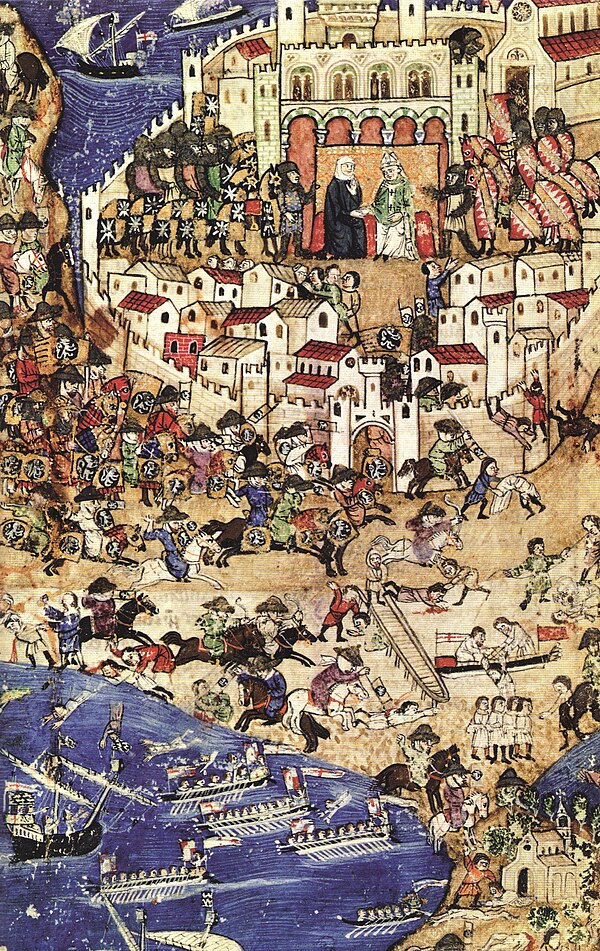

Ilghazi, awaiting reinforcements from Toghtekin of Damascus, surrounded Roger's camp on the night of June 27, exploiting the latter's vulnerable position in a wooded valley. Roger's force, comprising 700 knights, 500 Armenian cavalry, and 3,000 foot soldiers, including turcopoles, arranged into a V-shaped formation facing the Muslim forces, with a reserve unit under Renaud Mansoer.

The battle commenced on June 28 with an initial archery duel. The Crusader forces initially gained ground, especially on the right flank. However, the battle shifted as the left flank, under Robert of St. Lo, was overwhelmed, leading to disarray among the Crusaders, exacerbated by a north wind carrying dust into their faces.

The engagement concluded disastrously for the Crusaders, with Roger and the majority of his army either killed or captured; only two knights escaped. Roger's death marked a significant defeat, symbolized by his fall near the great jeweled cross, his standard. The aftermath saw Renaud Mansoer and potentially Walter the Chancellor among the captives, while the battlefield's carnage earned it the name "ager sanguinis" or "the field of blood."

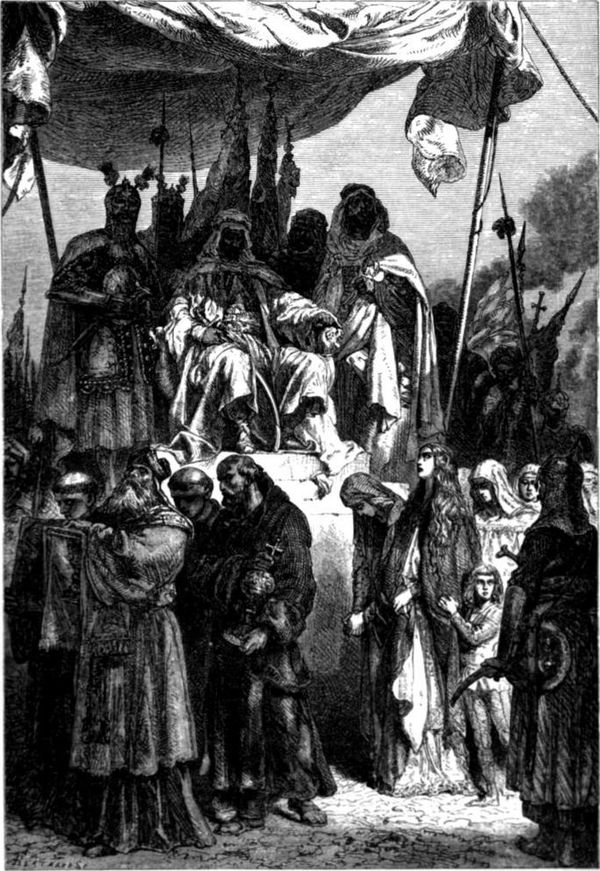

Following the battle, the Turks captured 70 knights and 500 lower-ranking soldiers. The high-ranking prisoners were ransomed, and 30 unable to afford their ransom were executed.

Aftermath

Ilghazi's victory, however, did not translate into further advances against Antioch, as he indulged in an alcoholic binge. Meanwhile, Patriarch Bernard of Antioch organized defenses as best he could, but the Antiochene field army's defeat led to the rapid fall of Atharib, Zerdana, Sarmin, Ma'arrat al-Numan, and Kafr Tab to Muslim forces.

Ilghazi's campaign was halted at the Battle of Hab on August 14, where he was defeated by Baldwin II of Jerusalem and Count Pons. Baldwin then took over the regency of Antioch and managed to recover some of the lost towns. Despite this recovery, the defeat at the Field of Blood significantly weakened Antioch, leaving it vulnerable to Muslim attacks in the ensuing decade and eventually under the influence of the Byzantine Empire. However, the Crusaders managed to regain some influence in Syria with their victory at the Battle of Azaz in 1125.