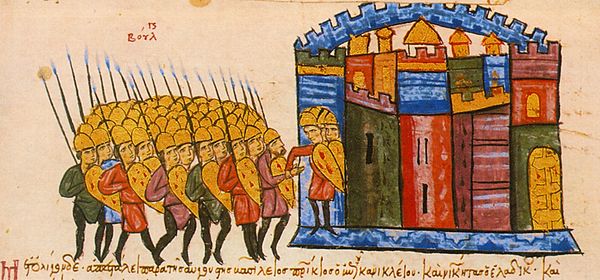

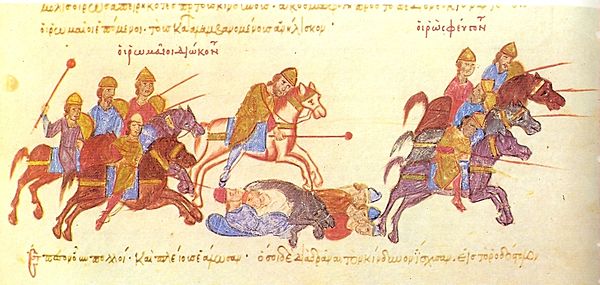

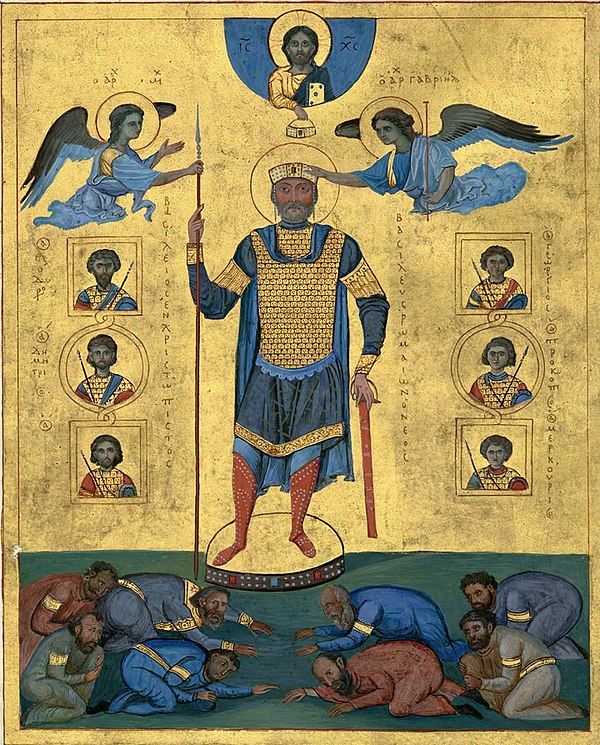

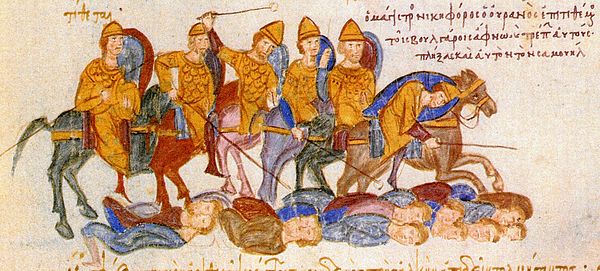

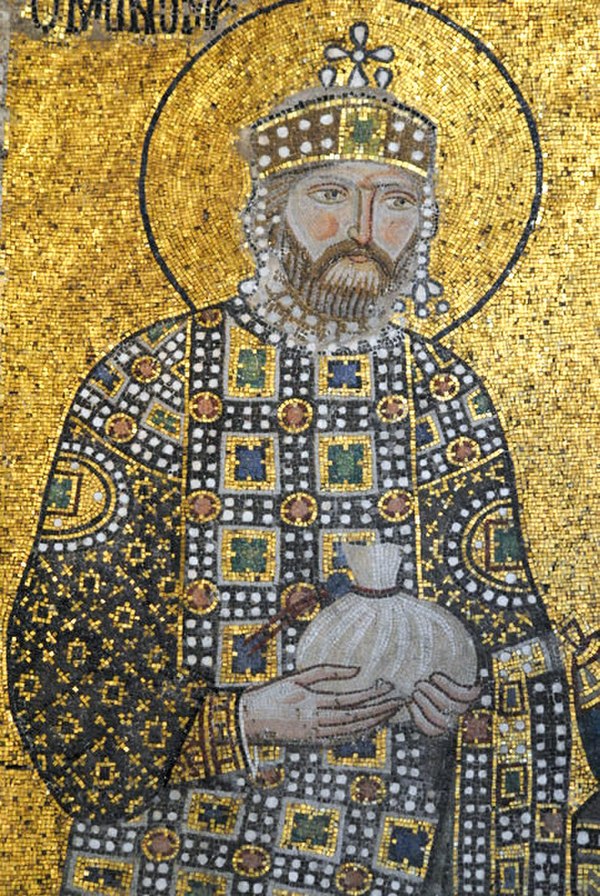

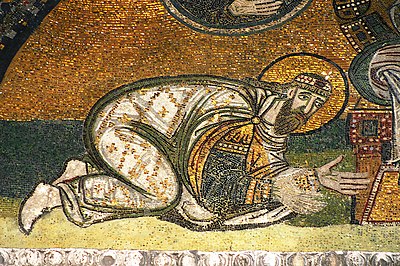

Following this Rus' distraction, in January 942 Kourkouas launched a new campaign in the East, which lasted for three years. The first assault fell on the territory of Aleppo, which was thoroughly plundered: at the fall of the town of Hamus, near Aleppo, even Arab sources record the capture of 10–15,000 prisoners by the Byzantines. Despite a minor counter-raid by Thamal or one of his retainers from Tarsus in the summer, in autumn Kourkouas launched another major invasion. At the head of an exceptionally large army, some 80,000 men according to Arab sources, he crossed from allied Taron into northern Mesopotamia. Mayyafiriqin, Amida, Nisibis, Dara—places where no Byzantine army had trod since the days of Heraclius 300 years earlier—were stormed and ravaged. The real aim of these campaigns, however, was Edessa, the repository of the "Holy Mandylion". This was a cloth believed to have been used by Christ to wipe his face, leaving an imprint of his features, and subsequently given to King Abgar V of Edessa. To the Byzantines, especially after the end of the Iconoclasm period and the restoration of image veneration, it was a relic of profound religious significance. As a result, its capture would provide the Lekapenos regime with an enormous boost in popularity and legitimacy.

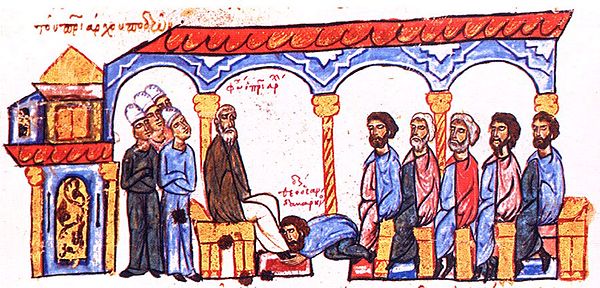

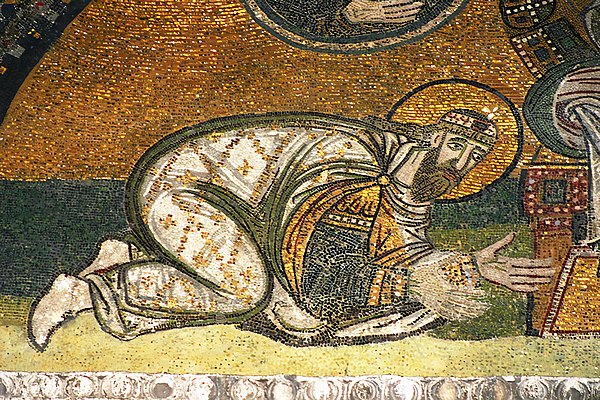

Kourkouas assailed Edessa every year from 942 onward and devastated its countryside, as he had done at Melitene. Finally, its emir agreed to a peace, swearing not to raise arms against Byzantium and to hand over the Mandylion in exchange for the return of 200 prisoners. The Mandylion was conveyed to Constantinople, where it arrived on August 15, 944, on the feast of the Dormition of the Theotokos. A triumphal entry was staged for the venerated relic, which was then deposited in the Theotokos of the Pharos church, the palatine chapel of the Great Palace. As for Kourkouas, he concluded his campaign by sacking Bithra (modern Birecik) and Germanikeia (modern Kahramanmaraş).