Aztecs

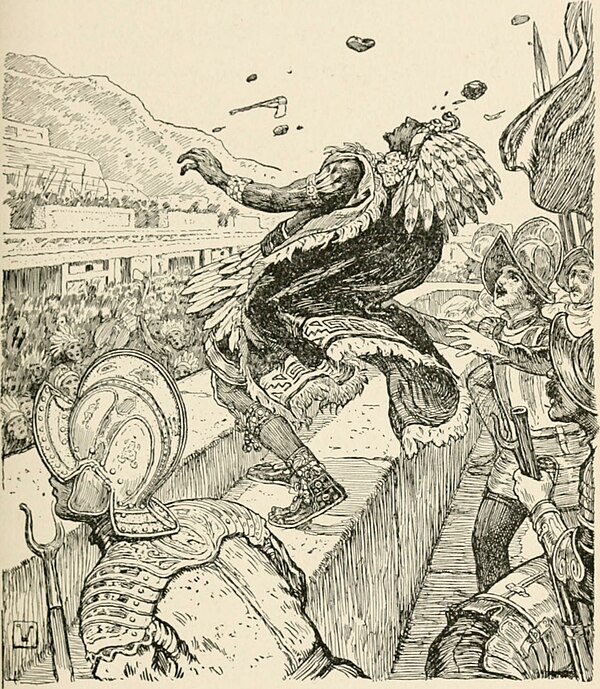

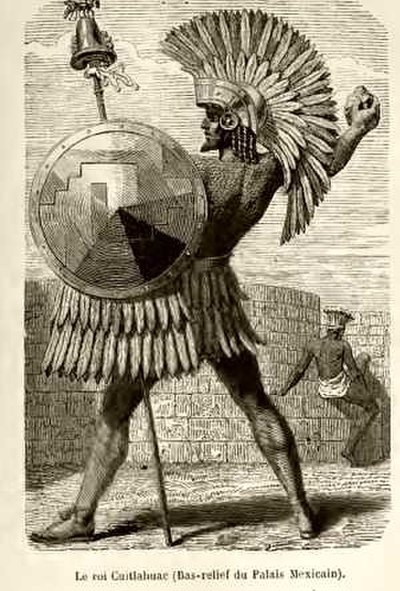

The Aztec Empire, also known as the Triple Alliance was a coalition of three Nahua city states; Mexico Tenochtitlan, Tetzcoco and Tlacopan. This alliance governed the region in and, around the Valley of Mexico from 1428 until they were defeated by the combined forces of conquistadors and their indigenous allies led by Hernán Cortés in 1521.

The formation of this alliance stemmed from factions that emerged victorious in a war between Azcapotzalco and its former tributary territories. While initially envisioned as an alliance of three city states Tenochtitlan eventually rose as the military power. By the time the Spanish expedition arrived in 1519 Tenochtitlan had assumed control over lands within the alliance while other members played supporting roles.

Following its establishment the Triple Alliance engaged in conquests and territorial expansions. At its peak it held sway over much of Mexico along with some regions in Mesoamerica like Xoconochco province—a distant Aztec territory, near todays Guatemalan border. Scholars have referred to governance as "hegemonic" or "indirect." The Aztecs maintained rulers, in cities on the condition that they paid tribute and provided military support when necessary. In exchange the imperial authority ensured protection, stability. Fostered a connected economic network among various regions with significant autonomy.

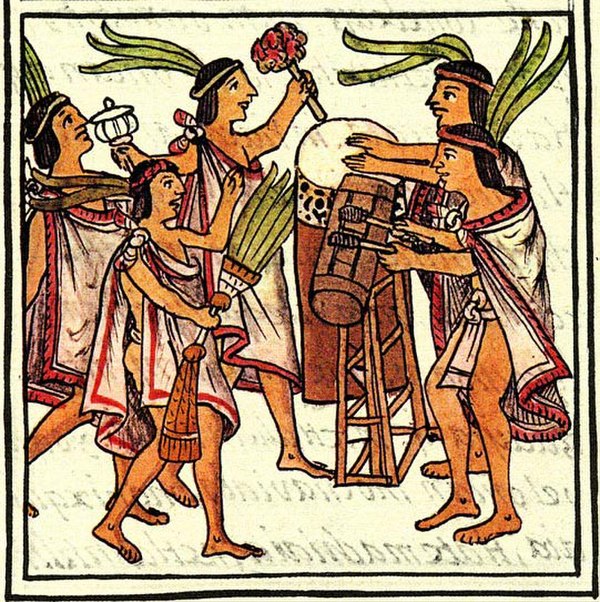

Aztec religion centered around a belief in teotl as the supreme deity Ometeotl alongside a pantheon of lesser gods and natural manifestations. While popular beliefs leaned towards mythology and polytheism the state religion of the empire encompassed both views held by elites and diverse beliefs endorsed by the populace. The empire officially acknowledged cults, particularly honoring the war deity Huītzilōpōchtli at the temple, in Tenochtitlan. Conquered peoples were permitted to practice their religions long as they incorporated Huītzilōpōchtli into their local pantheons.