Great Roman Civil War

Caesar's civil war (49–45 BCE) was one of the last politico-military conflicts of the Roman Republic before its reorganization into the Roman Empire. It began as a series of political and military confrontations between Gaius Julius Caesar and Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus.

Before the war, Caesar had led an invasion of Gaul for almost ten years. A build-up of tensions starting in late 49 BCE, with both Caesar and Pompey refusing to back down led, however, to the outbreak of civil war. Eventually, Pompey and his allies induced the Senate to demand Caesar give up his provinces and armies. Caesar refused and instead marched on Rome.

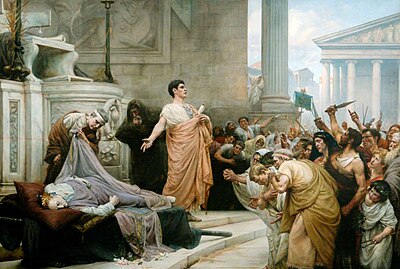

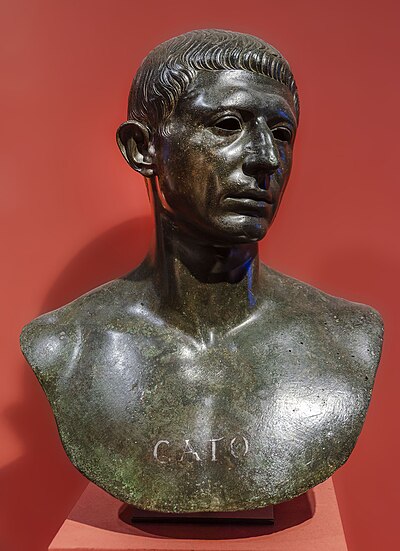

The war was a four-year-long politico-military struggle, fought in Italy, Illyria, Greece, Egypt, Africa, and Hispania. Pompey defeated Caesar in 48 BCE at the Battle of Dyrrhachium, but was himself defeated decisively at the Battle of Pharsalus. Many former Pompeians, including Marcus Junius Brutus and Cicero, surrendered after the battle, while others, such as Cato the Younger and Metellus Scipio fought on. Pompey fled to Egypt, where he was assassinated on arrival. Caesar intervened in Africa and Asia Minor before attacking North Africa, where he defeated Scipio in 46 BCE at the Battle of Thapsus. Scipio and Cato committed suicide shortly thereafter. The following year, Caesar defeated the last of the Pompeians under his former lieutenant Labienus in the Battle of Munda. He was made dictator perpetuo (dictator in perpetuity or dictator for life) in 44 BCE and, shortly thereafter, assassinated.