Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty, the last imperial dynasty of China, was established by the Manchus in 1636 and ruled China until its fall in 1912 following the Xinhai Revolution. Founded in Shenyang and expanding to Beijing in 1644, the Qing dynasty eventually assembled the territorial base for modern China, becoming the largest empire in Chinese history by area and the most populous nation globally by 1907.

Nurhaci, leader of the Manchus, initiated the formation by declaring independence from the Ming dynasty and founding the Later Jin dynasty in 1616. His son, Hong Taiji, officially proclaimed the Qing dynasty in 1636. The Qing's ascension to power was marked by the fall of Beijing to peasant rebels in 1644, which the Qing capitalized on by defeating the rebels and taking control with the aid of a Ming general.

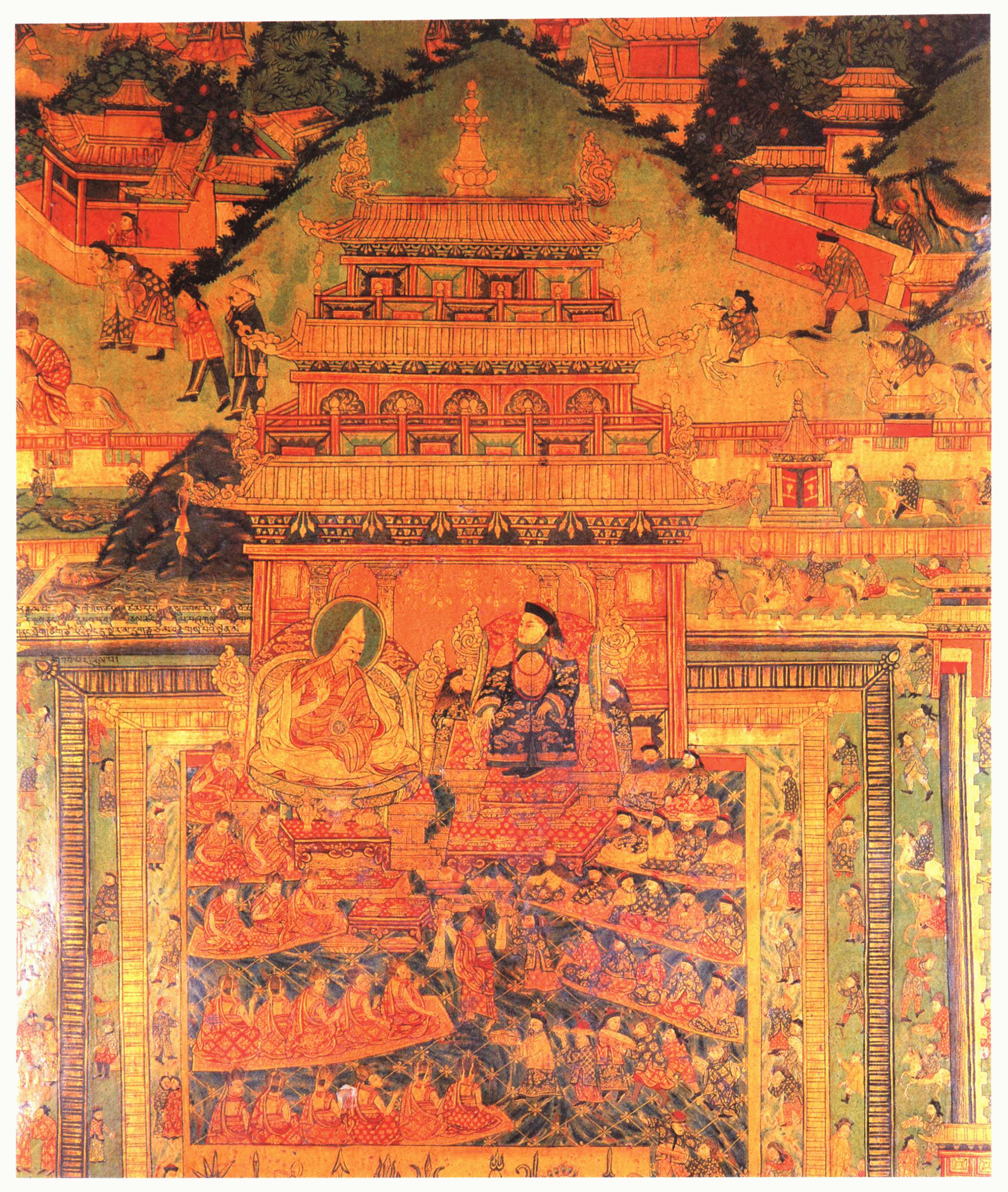

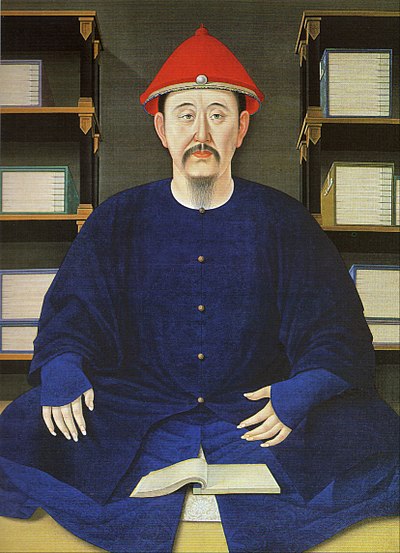

During the reign of the Kangxi Emperor (1661-1722), the dynasty solidified its power, promoting Confucian ideals, supporting Buddhism, and ensuring economic and population growth. Qing influence extended over peripheral countries and regions like Tibet, Mongolia, and Xinjiang, maintaining a tributary system.

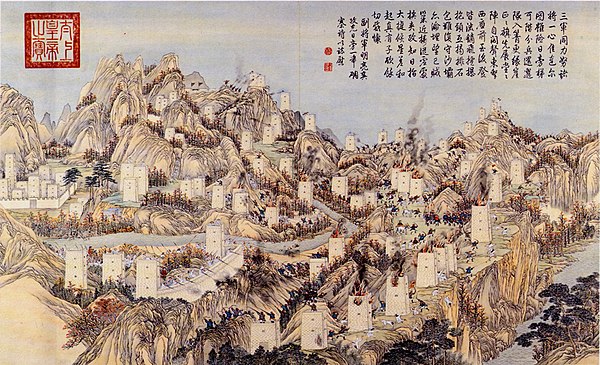

The peak of Qing power, the High Qing era, occurred under the Qianlong Emperor (1735–1796), known for his military campaigns and cultural patronage. Post-Qianlong, however, the dynasty faced numerous challenges including internal revolts, corruption, and external pressures that led to unfavorable treaties following military defeats in the Opium Wars.

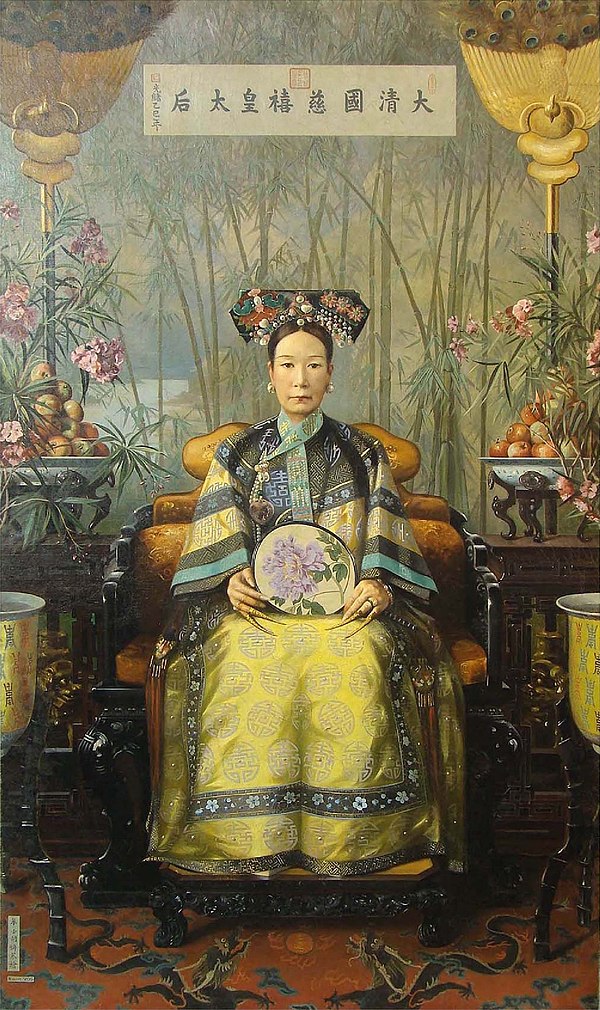

Economic and social unrest continued with significant upheavals such as the Taiping Rebellion and the Dungan Revolt, both causing extensive loss of life. Efforts to modernize through the Self-Strengthening Movement and the Hundred Days' Reform were largely unsuccessful, with conservative factions, particularly under Empress Dowager Cixi, resisting change.

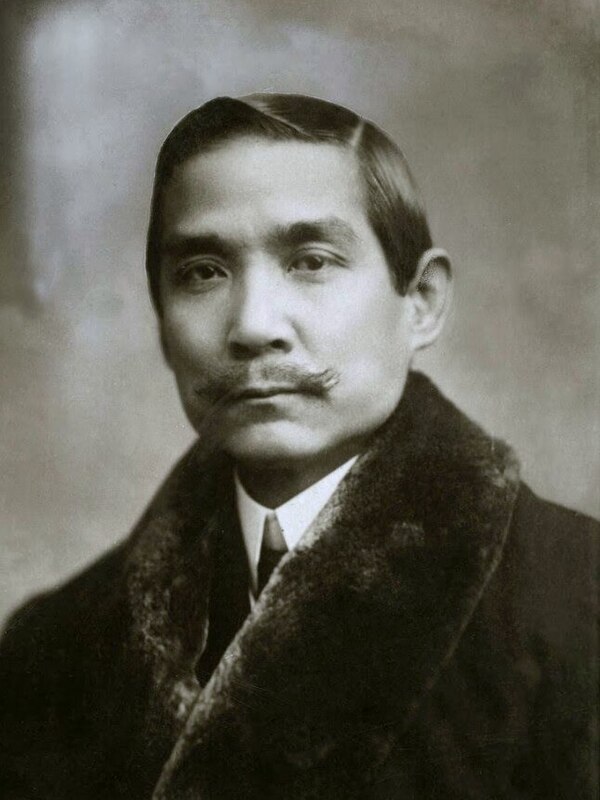

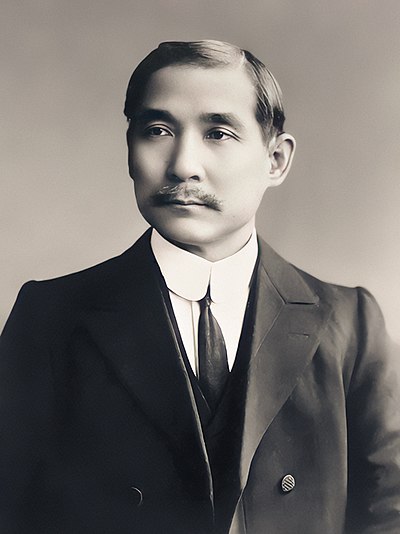

In response to anti-foreign sentiments exemplified by the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, the Qing initiated comprehensive reforms including fiscal changes and educational overhauls. However, these were too little and too late. The dynasty finally ended with the abdication of the Xuantong Emperor in 1912, briefly attempted a restoration in 1917, which failed, fully transitioning to the Republic of China era.