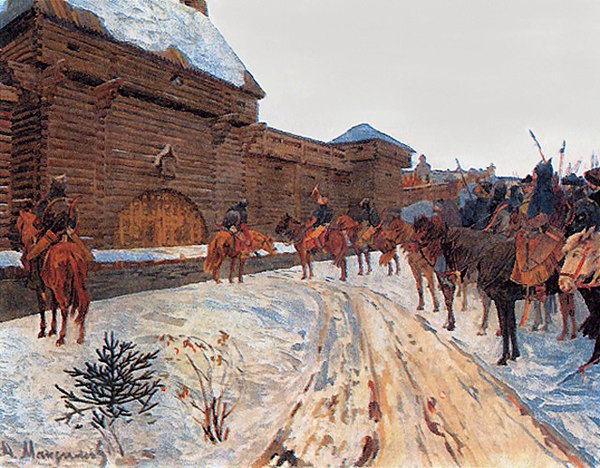

In 883, Prince Oleg conquered the Drevlians, imposing a fur tribute on them. By 885 he had subjugated the Poliane, Severiane, Vyatichi, and Radimichs, forbidding them to pay further tribute to the Khazars. Oleg continued to develop and expand a network of Rus' forts in Slav lands, begun by Rurik in the north.

The new Kievan state prospered due to its abundant supply of furs, beeswax, honey, and slaves for export, and because it controlled three main trade routes of Eastern Europe. In the north, Novgorod served as a commercial link between the Baltic Sea and the Volga trade route to the lands of the Volga Bulgars, the Khazars, and across the Caspian Sea as far as Baghdad, providing access to markets and products from Central Asia and the Middle East. Trade from the Baltic also moved south on a network of rivers and short portages along the Dnieper known as the "route from the Varangians to the Greeks," continuing to the Black Sea and on to Constantinople.

Kyiv was a central outpost along the Dnieper route and a hub with the east–west overland trade route between the Khazars and the Germanic lands of Central Europe. These commercial connections enriched Rus' merchants and princes, funding military forces and the construction of churches, palaces, fortifications, and further towns. Demand for luxury goods fostered production of expensive jewelry and religious wares, allowing their export, and an advanced credit and money-lending system may have also been in place.