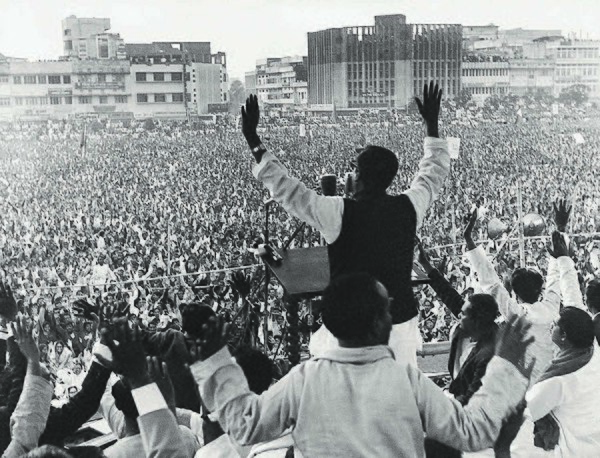

Upon his release on 10 January 1972, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman played a pivotal role in the newly independent Bangladesh, initially taking up the provisional presidency before becoming the Prime Minister. He led the consolidation of all governmental and decision-making bodies, with the politicians elected in the 1970 elections forming the provisional parliament.[16] The Mukti Bahini and other militias were integrated into the new Bangladeshi army, officially taking over from Indian forces on 17 March. Rahman's administration faced enormous challenges, including rehabilitating millions displaced by the 1971 conflict, addressing the aftermath of the 1970 cyclone, and revitalizing a war-ravaged economy.[16]

Under Rahman's leadership, Bangladesh was admitted to the United Nations and the Non-Aligned Movement. He sought international assistance by visiting countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, and signed a treaty of friendship with India, which provided significant economic and humanitarian support and helped in training Bangladesh's security forces.[17] Rahman established a close relationship with Indira Gandhi, appreciating India's support during the liberation war. His government undertook major efforts to rehabilitate around 10 million refugees, recover the economy, and avert a famine. In 1972, a new constitution was introduced, and subsequent elections solidified Mujib's power with his party securing an absolute majority. The administration emphasized expanding essential services and infrastructure, launching a five-year plan in 1973 focusing on agriculture, rural infrastructure, and cottage industries.[18]

Despite these efforts, Bangladesh faced a devastating famine from March 1974 to December 1974, considered one of the 20th century's deadliest. Initial signs appeared in March 1974, with rice prices soaring and Rangpur District experiencing the early impacts.[19] The famine resulted in the deaths of an estimated 27,000 to 1,500,000 people, highlighting the severe challenges faced by the young nation in its efforts to recover from the liberation war and natural disasters. The severe 1974 famine deeply influenced Mujib's approach to governance and led to a significant shift in his political strategy.[20] In the backdrop of mounting political unrest and violence, Mujib escalated his consolidation of power. On 25 January 1975, he declared a state of emergency, and through a constitutional amendment, banned all opposition political parties. Assuming the presidency, Mujib was granted unprecedented powers.[21] His regime established the Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (BAKSAL) as the sole legal political entity, positioning it as the representative of the rural populace, including farmers and laborers, and initiating socialist-oriented programs.[22]

At the peak of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's leadership, Bangladesh faced internal strife as the Jatiyo Samajtantrik Dal's military wing, Gonobahini, launched an insurgency aiming to establish a Marxist regime.[23] The government's response was to create the Jatiya Rakkhi Bahini, a force which soon became notorious for its severe human rights violations against civilians, including political assassinations,[24] extrajudicial killings by death squads,[25] and instances of rape.[26] This force operated with legal immunity, shielding its members from prosecution and other legal actions.[22] Despite retaining support from various population segments, Mujib's actions, particularly the use of force and restriction of political freedoms, led to discontent among liberation war veterans. They viewed these measures as a departure from the ideals of democracy and civil rights that motivated Bangladesh's struggle for independence.