Kingdom of Hungary (Late Medieval)

In the Late Middle Ages, the Kingdom of Hungary, a country in Central Europe, experienced a period of interregnum in the early 14th century. Royal power was restored under Charles I (1308–1342), a scion of the Capetian House of Anjou. Gold and silver mines opened in his reign produced about one third of the world's total production up until the 1490s. The kingdom reached the peak of its power under Louis the Great (1342–1382) who led military campaigns against Lithuania, southern Italy and other faraway territories.

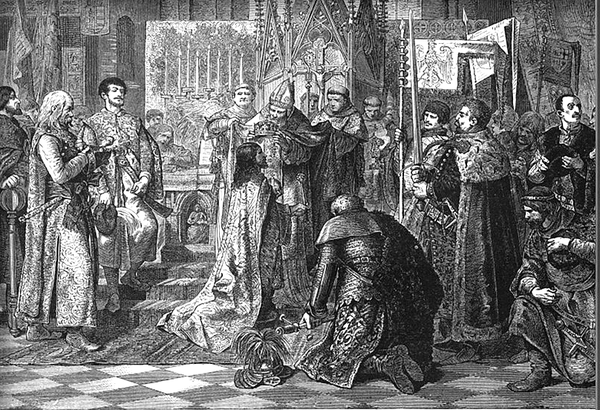

The expansion of the Ottoman Empire reached the kingdom under Sigismund of Luxemburg (1387–1437). In the next decades, a talented military commander, John Hunyadi, directed the fight against the Ottomans. His victory at Nándorfehérvár (present-day Belgrade, Serbia) in 1456 stabilized the southern frontiers for more than half a century. The first king of Hungary without dynastic ancestry was Matthias Corvinus (1458–1490), who led several successful military campaigns and also became the King of Bohemia and the Duke of Austria. With his patronage Hungary became the first country which adopted the Renaissance from Italy.