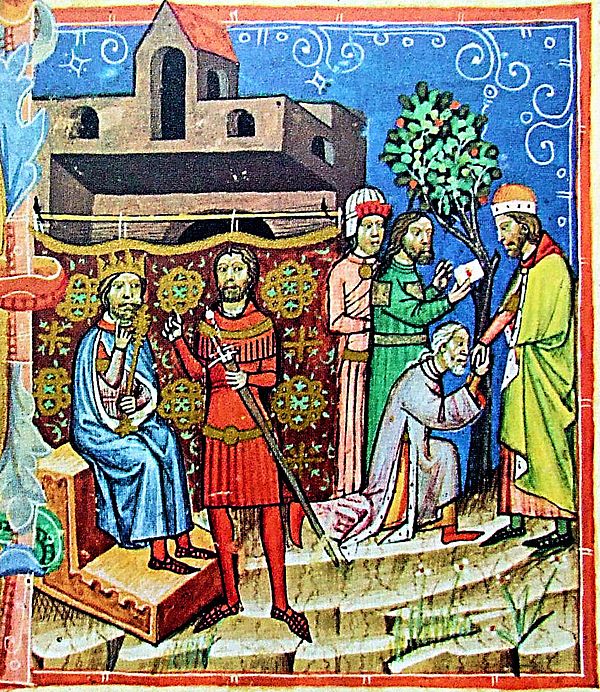

The 1282 Cuman rebellion may have catalyzed the Mongol invasion. Cuman warriors driven out of Hungary offered their services to Nogai Khan, de facto head of the Golden Horde, and told him about the perilous political situation in Hungary. Seeing this as an opportunity, Nogai decided to start a vast campaign against the apparently weak kingdom.

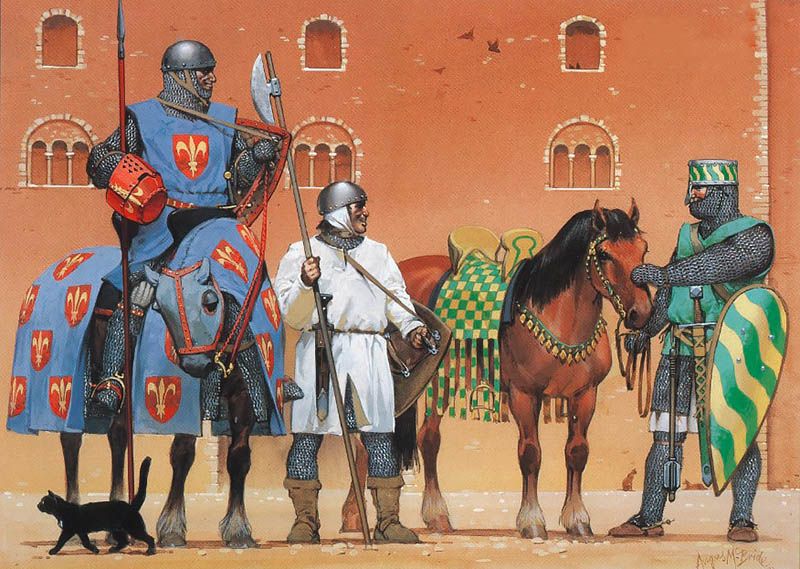

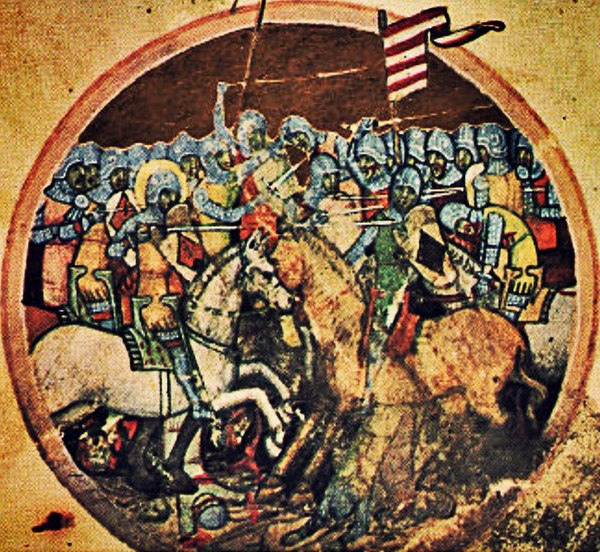

In the winter of 1285, Mongol armies invaded Hungary for a second time. As in the first invasion in 1241, Mongols invaded Hungary in two fronts. Nogai invaded via Transylvania, while Talabuga invaded via Transcarpathia and Moravia. A third, smaller force likely entered the center of the kingdom, mirroring Kadan's earlier route. The invasion paths seemed to mirror those taken by Batu and Subutai 40 years earlier, with Talabuga going through Verecke Pass and Nogai going through Brassó to enter Transylvania. Much like the first invasion, the Mongols emphasized speed and surprise and intended to destroy the Hungarian forces in detail, invading in winter for hope of catching the Hungarians off guard and moving fast enough that it was impossible (at least until their later setbacks) for Ladislaus to gather enough men to engage them in a decisive confrontation. Because of the lack of civil war in the Mongol Empire at the time, as well as the lack of any other major conflicts involving the Golden Horde, Nogai was able to field a very large army for this invasion, with the Galician-Volhynian Chronicle describing it as "a great host" but its exact size isn't certain. It is known that the Mongol host included cavalry from their vassals, the Ruthenian princes, including Lev Daniilovich and others from among their Rus′ satellites.

The results of the invasion could not have contrasted more sharply with those of the 1241 invasion. The invasion was repelled handily, and the Mongols lost much of their invading force due to several months of starvation, numerous small raids, and two major military defeats. This was mostly thanks to the new fortification network and the military reforms. No major invasion of Hungary would be launched after the failure of the campaign of 1285, though small raids from the Golden Horde were frequent well into the 14th century.

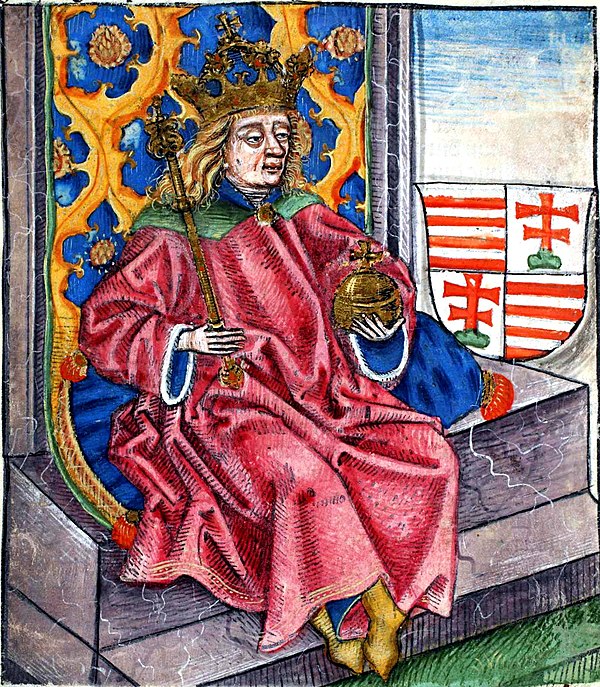

While a victory for Hungary overall (albeit with heavy civilian casualties), the war was a political disaster for the king. Like his grandfather before him, many nobles accused him of inviting the Mongols into his lands, due to his perceived ties to the Cumans.

.JPG/600px-Byzantine_Greek_Alexander_Manuscript_Cataphract_(cropped).JPG)