Grand Principality of Serbia

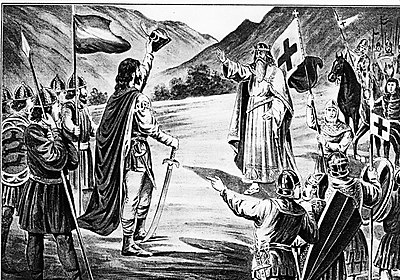

Grand Principality of Serbia was a medieval Serbian state that existed from the second half of the 11th century up until 1217, when it was transformed into the Kingdom of Serbia. Initially, the Grand Principality of Serbia emerged in the historical region of Raška, and gradually expanded, during the 12th century, encompassing various neighboring regions, including territories of modern Montenegro, Herzegovina, and southern Dalmatia. It was founded by Grand Prince Vukan, who initially (c. 1082) served as regional governor of Raška, appointed by King Constantine Bodin. During Byzantine-Serbian wars (c. 1090) Vukan gained prominence and became self-governing ruler in inner Serbian regions. He founded the Vukanović dynasty, that ruled the Grand Principality. Through diplomatic ties with the Kingdom of Hungary, Vukan′s successors managed to retain their self-governance, while also recognizing the supreme overlordship of the Byzantine Empire, up to 1180. Grand Prince Stefan Nemanja (1166–1196) gained full independence and united almost all Serbian lands. His son, Grand Prince Stefan was crowned King of Serbia in 1217, while his younger son Saint Sava became the first Archbishop of Serbs, in 1219.