Battle of Gettysburg

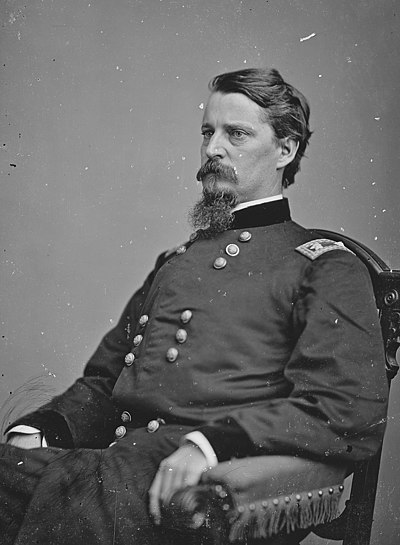

The Battle of Gettysburg was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Potomac defeated attacks by Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, halting Lee's invasion of the North. The battle involved the largest number of casualties of the entire war and is often described as the war's turning point due to the Union's decisive victory and concurrence with the Siege of Vicksburg.

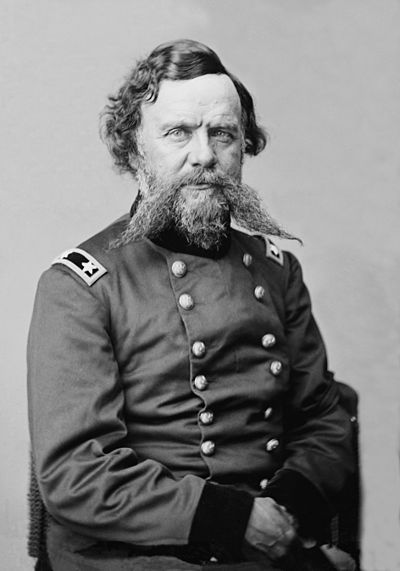

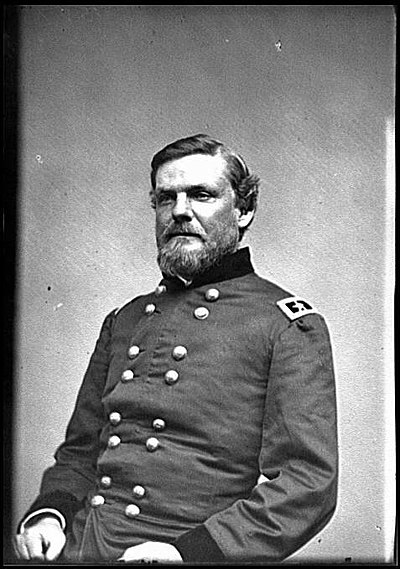

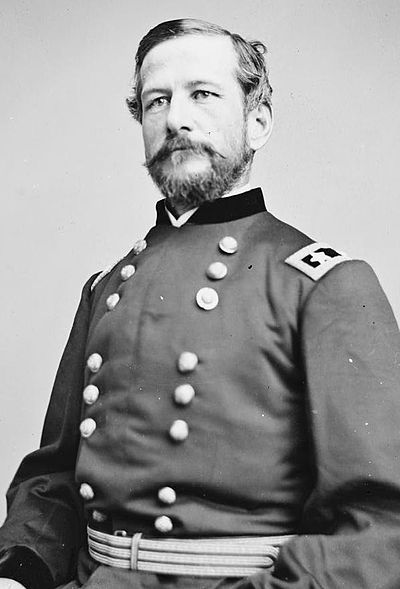

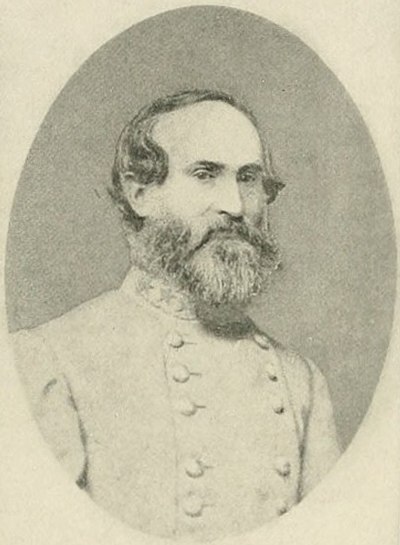

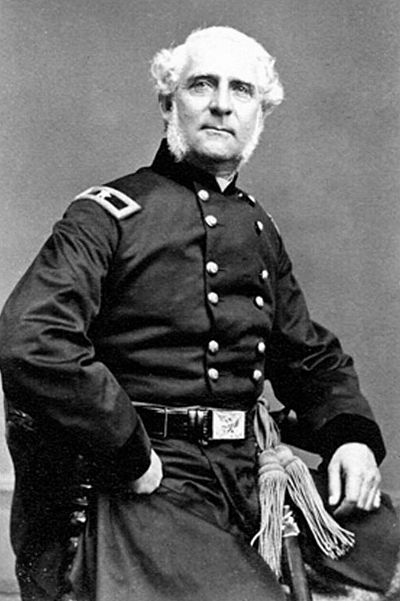

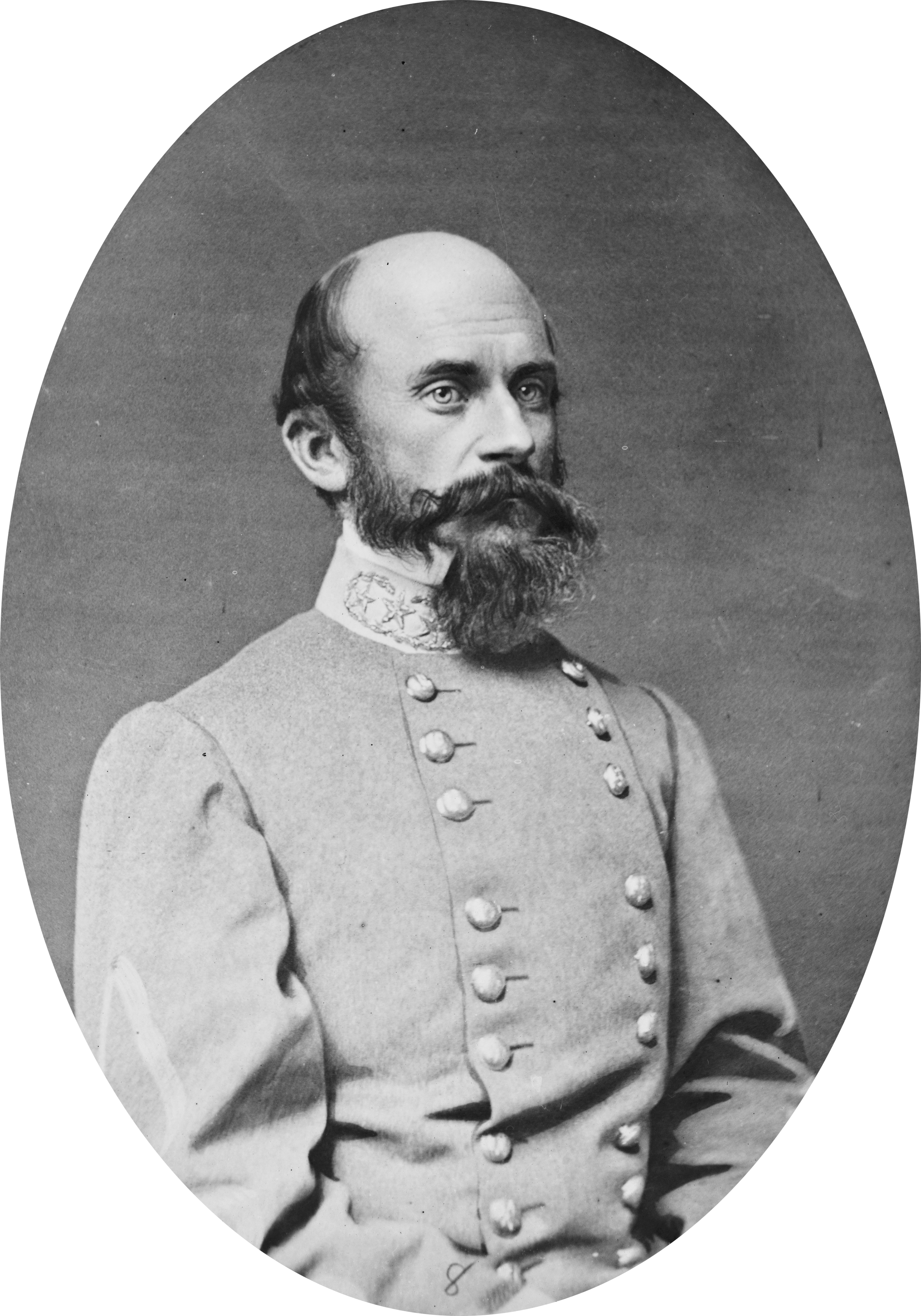

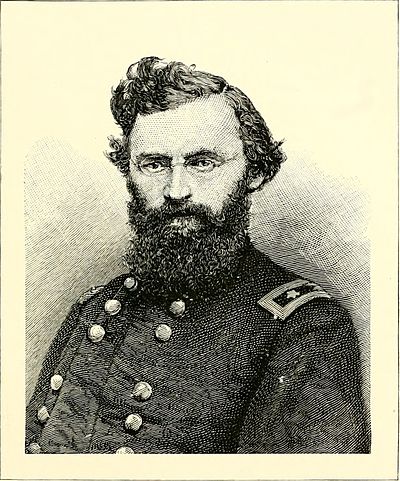

After his success at Chancellorsville in Virginia in May 1863, Lee led his army through the Shenandoah Valley to begin his second invasion of the North—the Gettysburg Campaign. With his army in high spirits, Lee intended to shift the focus of the summer campaign from war-ravaged northern Virginia and hoped to influence Northern politicians to give up their prosecution of the war by penetrating as far as Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, or even Philadelphia. Prodded by President Abraham Lincoln, Major General Joseph Hooker moved his army in pursuit, but was relieved of command just three days before the battle and replaced by Meade.

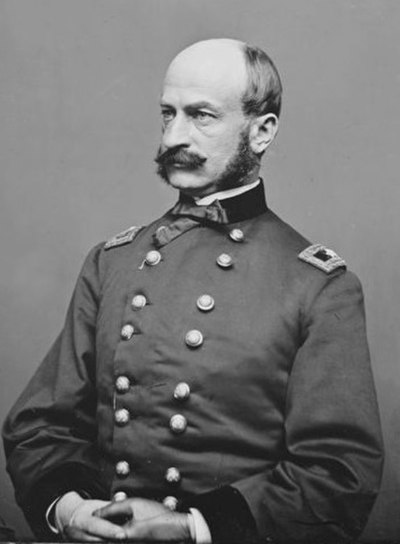

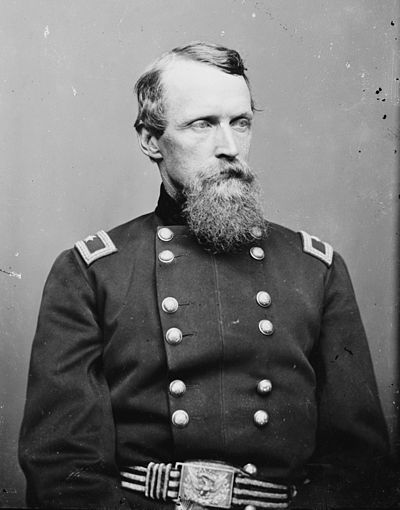

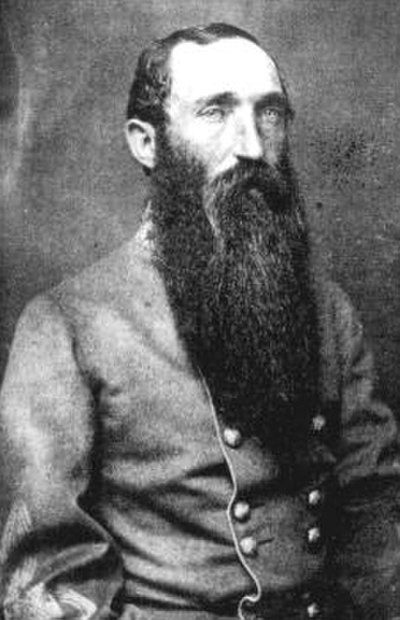

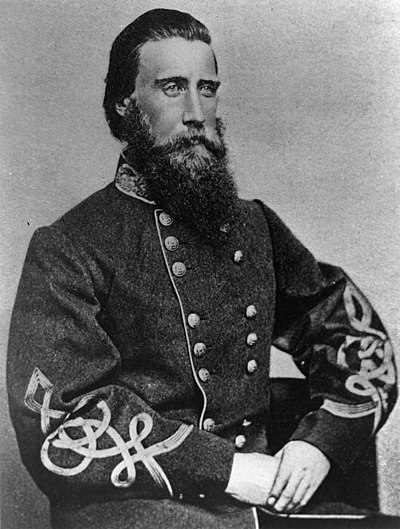

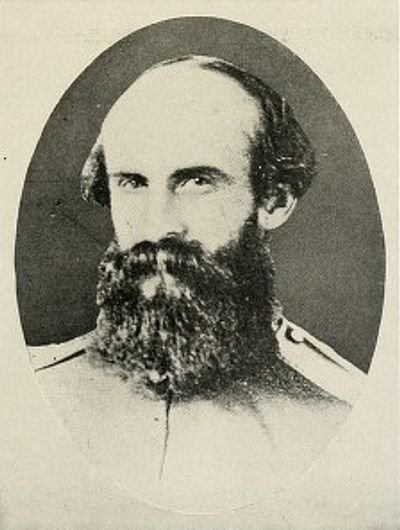

Elements of the two armies initially collided at Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, as Lee urgently concentrated his forces there, his objective being to engage the Union army and destroy it. Low ridges to the northwest of town were defended initially by a Union cavalry division under Brigadier General John Buford, and soon reinforced with two corps of Union infantry. However, two large Confederate corps assaulted them from the northwest and north, collapsing the hastily developed Union lines, sending the defenders retreating through the streets of the town to the hills just to the south. On the second day of battle, most of both armies had assembled. The Union line was laid out in a defensive formation resembling a fishhook. In the late afternoon of July 2, Lee launched a heavy assault on the Union left flank, and fierce fighting raged at Little Round Top, the Wheatfield, Devil's Den, and the Peach Orchard. On the Union right, Confederate demonstrations escalated into full-scale assaults on Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill. All across the battlefield, despite significant losses, the Union defenders held their lines.

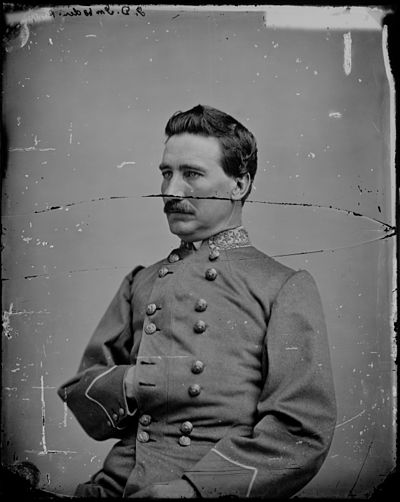

On the third day of battle, fighting resumed on Culp's Hill, and cavalry battles raged to the east and south, but the main event was a dramatic infantry assault by around 12,000 Confederates against the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge, known as Pickett's Charge. The charge was repelled by Union rifle and artillery fire, at great loss to the Confederate army. Lee led his army on a torturous retreat back to Virginia. Between 46,000 and 51,000 soldiers from both armies were casualties in the three-day battle, the most costly in US history. On November 19, President Lincoln used the dedication ceremony for the Gettysburg National Cemetery to honor the fallen Union soldiers and redefine the purpose of the war in his historic Gettysburg Address.