Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam, or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union Gen. George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac near Sharpsburg, Maryland, and Antietam Creek. Part of the Maryland Campaign, it was the first field army–level engagement in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War to take place on Union soil. It remains the bloodiest day in American history, with a combined tally of 22,727 dead, wounded, or missing. Although the Union army suffered heavier casualties than the Confederates, the battle was a major turning point in the Union's favor.

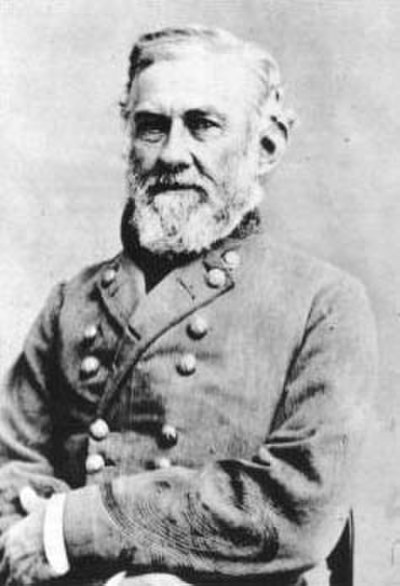

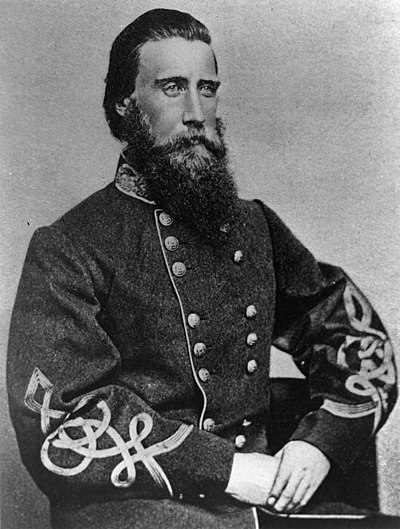

After pursuing Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee into Maryland, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan of the Union Army launched attacks against Lee's army who were in defensive positions behind Antietam Creek. At dawn on September 17, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker's corps mounted a powerful assault on Lee's left flank. Attacks and counterattacks swept across Miller's Cornfield, and fighting swirled around the Dunker Church. Union assaults against the Sunken Road eventually pierced the Confederate center, but the Federal advantage was not followed up. In the afternoon, Union Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside's corps entered the action, capturing a stone bridge over Antietam Creek and advancing against the Confederate right. At a crucial moment, Confederate Maj. Gen. A. P. Hill's division arrived from Harpers Ferry and launched a surprise counterattack, driving back Burnside and ending the battle. Although outnumbered two-to-one, Lee committed his entire force, while McClellan sent in less than three-quarters of his army, enabling Lee to fight the Federals to a standstill. During the night, both armies consolidated their lines. In spite of crippling casualties, Lee continued to skirmish with McClellan throughout September 18, while removing his battered army south of the Potomac River.

McClellan successfully turned Lee's invasion back, making the battle a Union victory, but President Abraham Lincoln, unhappy with McClellan's general pattern of over caution and his failure to pursue the retreating Lee, relieved McClellan of command in November. From a tactical standpoint, the battle was somewhat inconclusive; the Union army successfully repelled the Confederate invasion but suffered heavier casualties and failed to defeat Lee's army outright. However, it was a significant turning point in the war in favor of the Union due in large part to its political ramifications: the battle's result gave Lincoln the political confidence to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring all those held as slaves within enemy territory free. This effectively discouraged the British and French governments from recognizing the Confederacy, as neither power wished to give the appearance of supporting slavery.