Kingdom of Poland

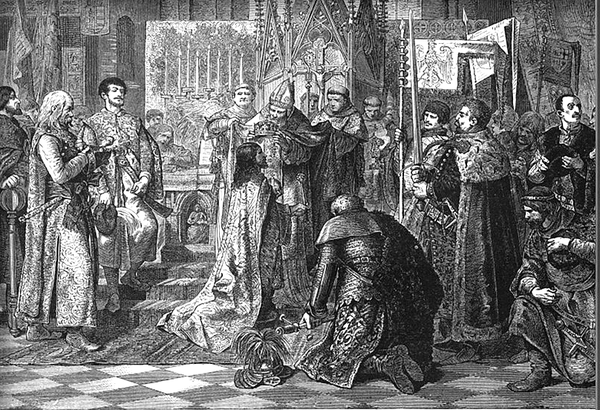

The period of rule by the Piast dynasty between the 10th and 14th centuries is the first major stage of the history of the Polish state. It was Mieszko I, the son of Siemomysł, who is now considered the proper founder of the Polish state at about 960 AD. The ruling house then remained in power in the Polish lands until 1370. Mieszko converted to Christianity of the Western Latin Rite in an event known as the Baptism of Poland in 966. He also completed a unification of the Lechitic tribal lands that was fundamental to the existence of the new country of Poland. Mieszko's son Bolesław I the Brave, pursued territorial conquests and was officially crowned in 1025 as the first king of Poland.

Bolesław III, the last duke of the early period, succeeded in defending his country and recovering territories previously lost. Upon his death in 1138, Poland was divided among his sons. The resulting internal fragmentation eroded the initial Piast monarchical structure in the 12th and 13th centuries and caused fundamental and lasting changes. Konrad I of Masovia invited the Teutonic Knights to help him fight the Baltic Prussian pagans, which led to centuries of Poland's warfare with the Knights and the German Prussian state.

In 1320, the kingdom was restored under Władysław I the Elbow-high, then strengthened and expanded by his son Casimir III the Great. The western provinces of Silesia and Pomerania were lost after the fragmentation, and Poland began expanding to the east. The period ended with the reigns of two members of the Capetian House of Anjou between 1370 and 1384. The consolidation in the 14th century laid the base for the new powerful kingdom of Poland that was to follow.