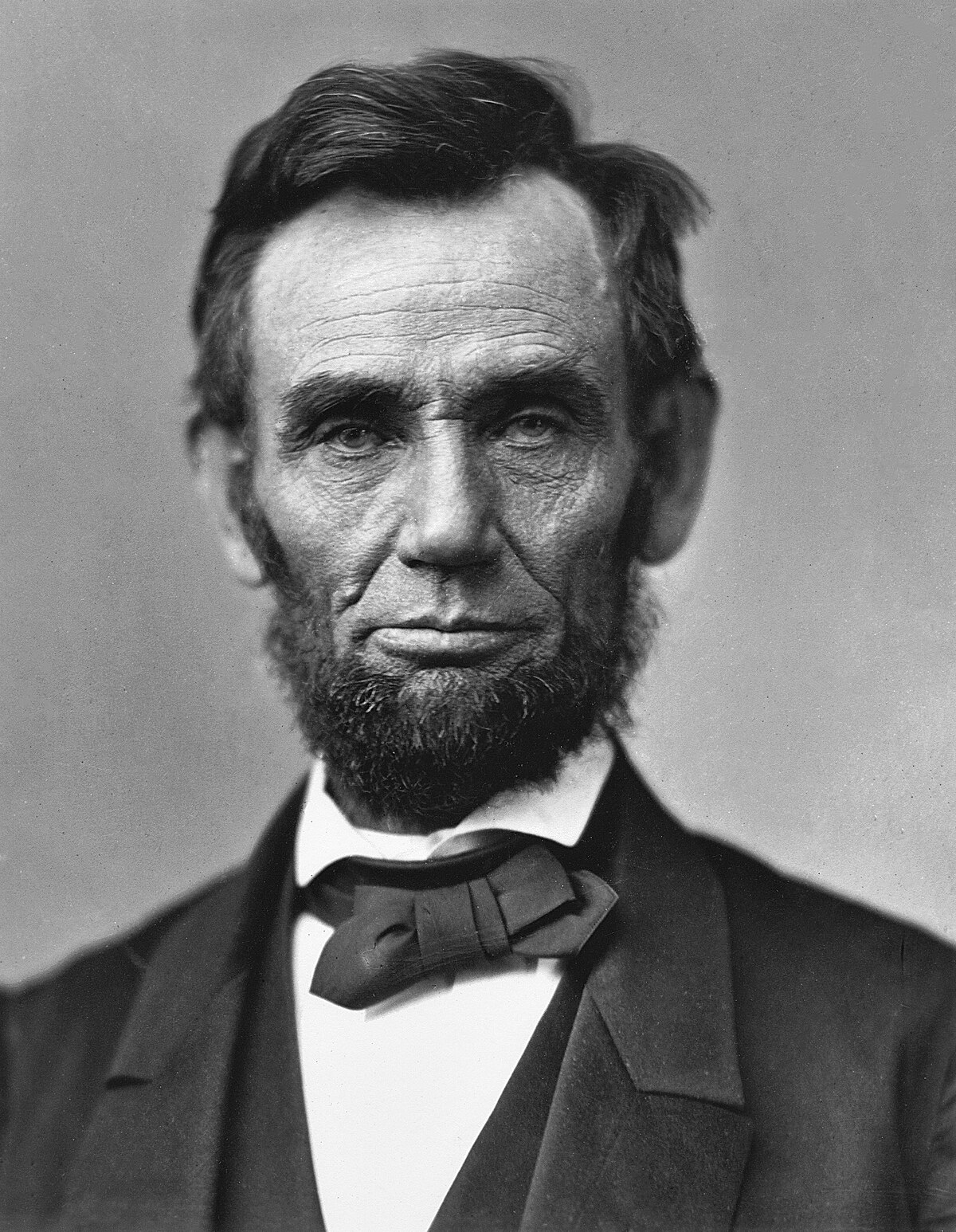

Abraham Lincoln

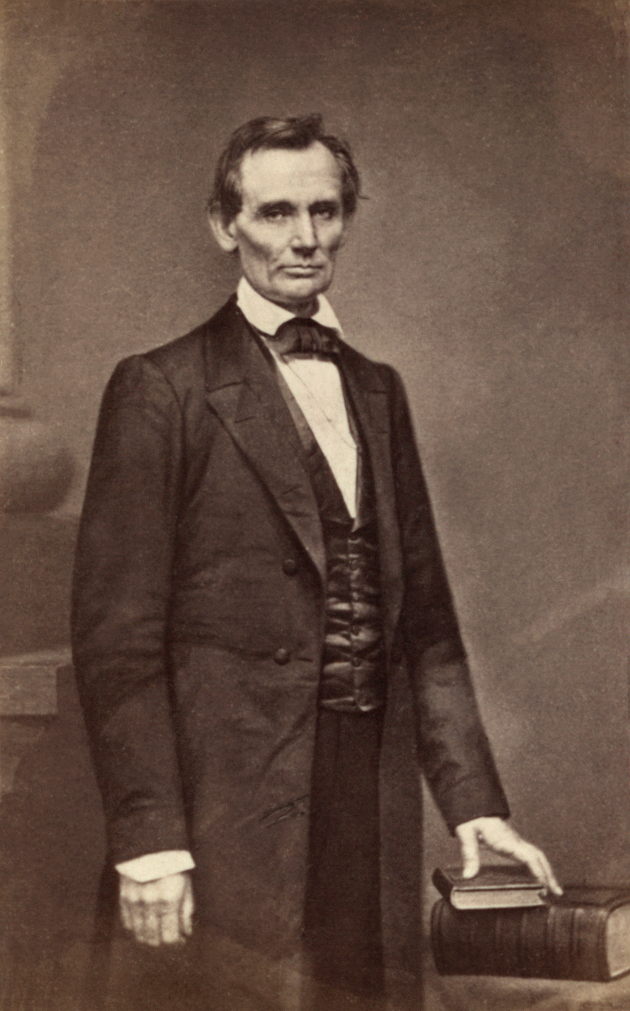

Abraham Lincoln was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the Union through the American Civil War to defend the nation as a constitutional union and succeeded in abolishing slavery, bolstering the federal government, and modernizing the U.S. economy.

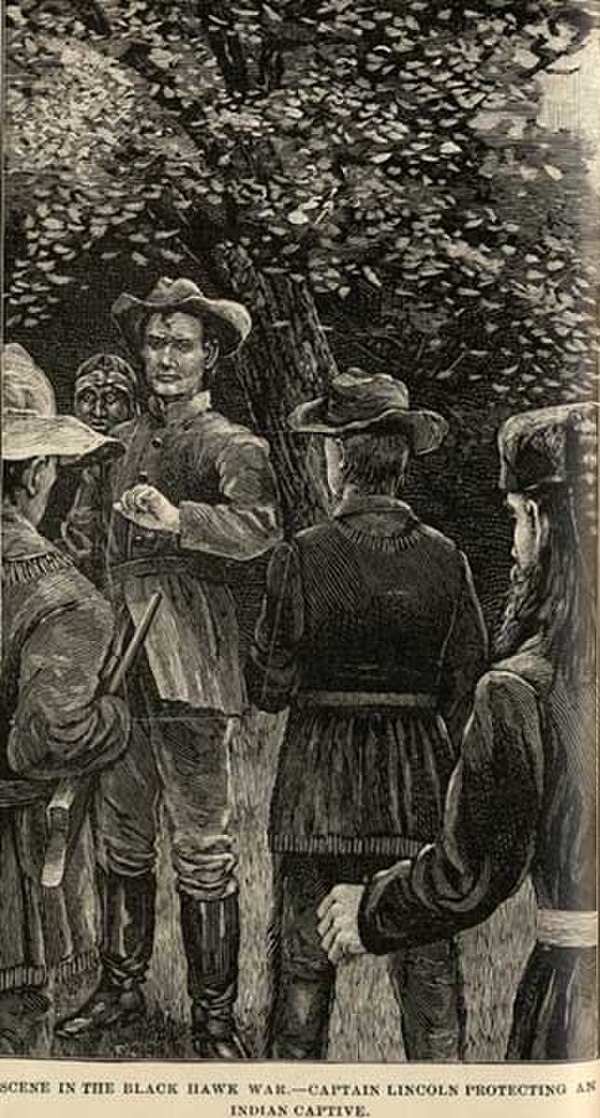

Lincoln was born into poverty in a log cabin in Kentucky and was raised on the frontier, primarily in Indiana. He was self-educated and became a lawyer, Whig Party leader, Illinois state legislator, and U.S. Congressman from Illinois. In 1849, he returned to his successful law practice in central Illinois. In 1854, he was angered by the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which opened the territories to slavery, and he re-entered politics. He soon became a leader of the new Republican Party. He reached a national audience in the 1858 Senate campaign debates against Stephen A. Douglas. Lincoln ran for president in 1860, sweeping the North to gain victory. Pro-slavery elements in the South viewed his election as a threat to slavery, and Southern states began seceding from the nation. During this time, the newly formed Confederate States of America began seizing federal military bases in the south. Just over one month after Lincoln assumed the presidency, the Confederate States attacked Fort Sumter, a U.S. fort in South Carolina. Following the bombardment, Lincoln mobilized forces to suppress the rebellion and restore the union.

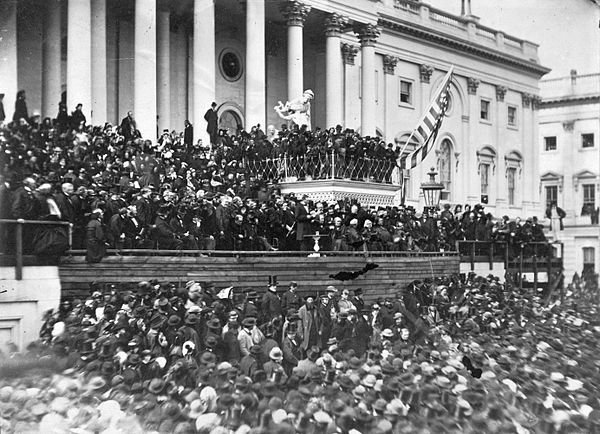

Lincoln, a moderate Republican, had to navigate a contentious array of factions with friends and opponents from both the Democratic and Republican parties. His allies, the War Democrats and the Radical Republicans, demanded harsh treatment of the Southern Confederates. Anti-war Democrats (called "Copperheads") despised Lincoln, and irreconcilable pro-Confederate elements plotted his assassination. He managed the factions by exploiting their mutual enmity, carefully distributing political patronage, and by appealing to the American people. His Gettysburg Address came to be seen as one of the greatest and most influential statements of American national purpose. Lincoln closely supervised the strategy and tactics in the war effort, including the selection of generals, and implemented a naval blockade of the South's trade. He suspended habeas corpus in Maryland and elsewhere, and averted British intervention by defusing the Trent Affair. In 1863, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared the slaves in the states "in rebellion" to be free. It also directed the Army and Navy to "recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons" and to receive them "into the armed service of the United States." Lincoln also pressured border states to outlaw slavery, and he promoted the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which upon its ratification abolished slavery.

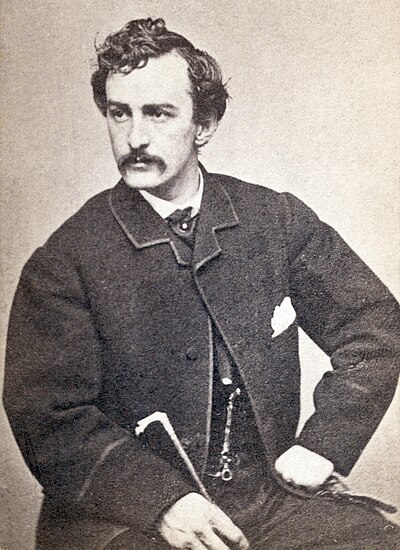

Lincoln managed his own successful re-election campaign. He sought to heal the war-torn nation through reconciliation. On April 14, 1865, just five days after the war's end at Appomattox, he was attending a play at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., with his wife, Mary, when he was fatally shot by Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth. Lincoln is remembered as a martyr and a national hero for his wartime leadership and for his efforts to preserve the Union and abolish slavery. Lincoln is often ranked in both popular and scholarly polls as the greatest president in American history.