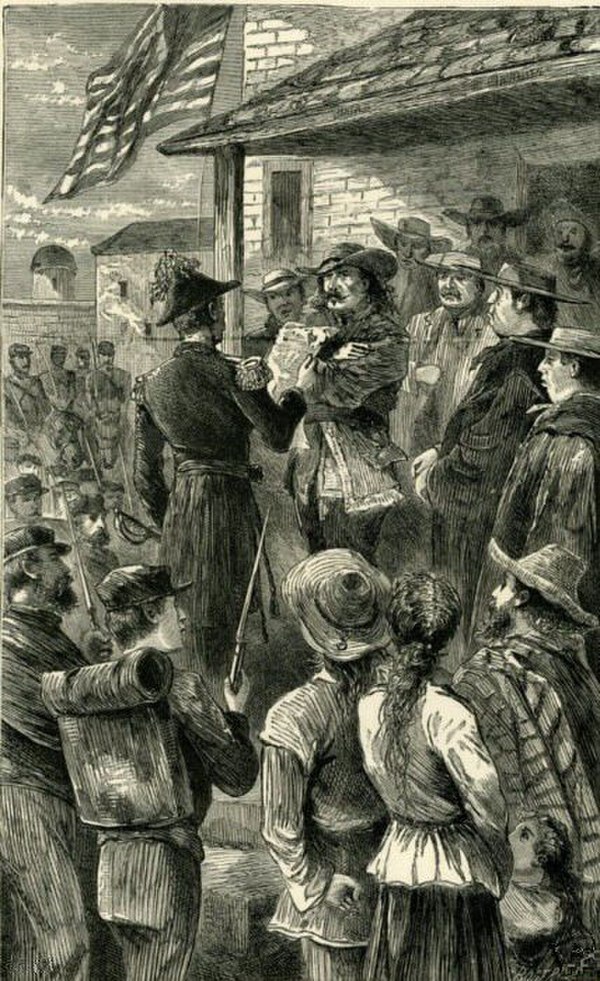

Following the capture of the capital, the Mexican government moved to the temporary capital at Querétaro. In Mexico City, U.S. forces became an army of occupation and subject to stealth attacks from the urban population. Conventional warfare gave way to guerrilla warfare by Mexicans defending their homeland. They inflicted significant casualties on the U.S. Army, particularly on soldiers slow to keep up.

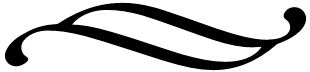

General Scott sent about a quarter of his strength to secure his line of communications to Veracruz from the Light Corps of General Rea and other Mexican guerrilla forces that had made stealth attacks since May. Mexican guerrillas often tortured and mutilated the bodies of the U.S. troops, as revenge and warning. Americans interpreted these acts not as Mexicans' defense of their patria, but as evidence of Mexicans' brutality as racial inferiors. For their part, U.S. soldiers took revenge on Mexicans for the attacks, whether or not they were individually suspected of guerrilla acts.

Scott viewed guerrilla attacks as contrary to the "laws of war" and threatened the property of populations that appeared to harbor the guerrillas. Captured guerrillas were to be shot, including helpless prisoners, with the reasoning that the Mexicans did the same. Historian Peter Guardino contends that the U.S. Army command was complicit in the attacks against Mexican civilians. By threatening the civilian populations' homes, property, and families with burning whole villages, looting, and raping women, the U.S. Army separated guerrillas from their base. "Guerrillas cost the Americans dearly, but indirectly cost Mexican civilians more."

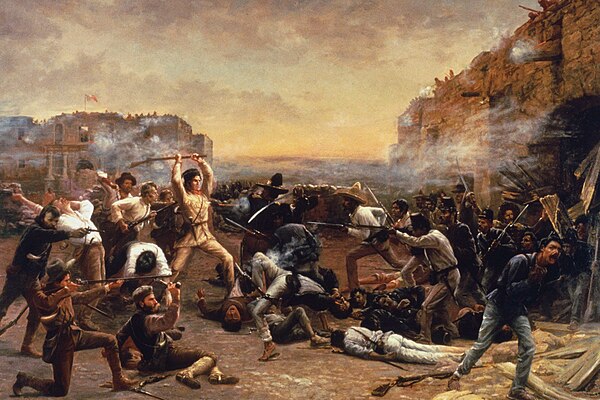

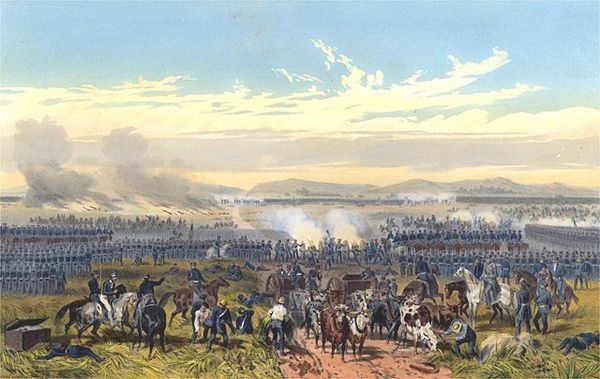

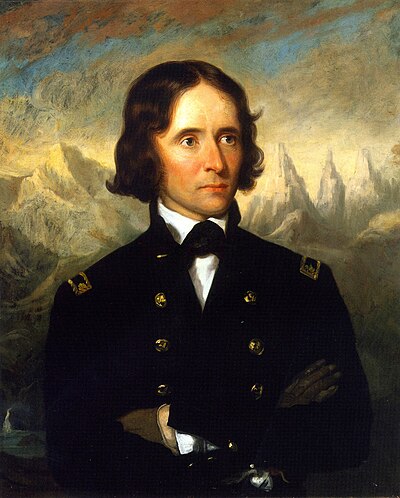

Scott strengthened the garrison of Puebla and by November had added a 1,200-man garrison at Jalapa, established 750-man posts along the main route between the port of Veracruz and the capital, at the pass between Mexico City and Puebla at Rio Frio, at Perote and San Juan on the road between Jalapa and Puebla, and at Puente Nacional between Jalapa and Veracruz. He had also detailed an anti-guerrilla brigade under Lane to carry the war to the Light Corps and other guerrillas. He ordered that convoys would travel with at least 1,300-man escorts. Victories by Lane over the Light Corps at Atlixco (October 18, 1847), at Izúcar de Matamoros (November 23, 1847), and at Galaxara Pass (November 24, 1847) weakened General Rea's forces.

Later a raid against the guerrillas of Padre Jarauta at Zacualtipan (February 25, 1848) further reduced guerrilla raids on the American line of communications. After the two governments concluded a truce to await ratification of the peace treaty, on March 6, 1848, formal hostilities ceased. However, some bands continued in defiance of the Mexican government until the U.S. Army's evacuation in August. Some were suppressed by the Mexican Army or, like Padre Jarauta, executed.