Edward I was now free from embarrassment abroad and at home, and having made preparations for the final conquest of Scotland, he commenced his invasion in the middle of May 1303. His army was arranged in two divisions—one under himself and the other under the Prince of Wales. Edward advanced in the east and his son entered Scotland by the west, but his advance was checked at several points by Wallace. King Edward reached Edinburgh by June, then marched by Linlithgow and Stirling to Perth. Comyn, with the small force under his command, could not hope to defeat Edward's forces. Edward stayed in Perth until July, then proceeded, via Dundee, Montrose and Brechin, to Aberdeen, arriving in August. From there, he marched through Moray, before his progress continued to Badenoch, before re-tracing his path back south to Dunfermline, where he stayed through the winter.

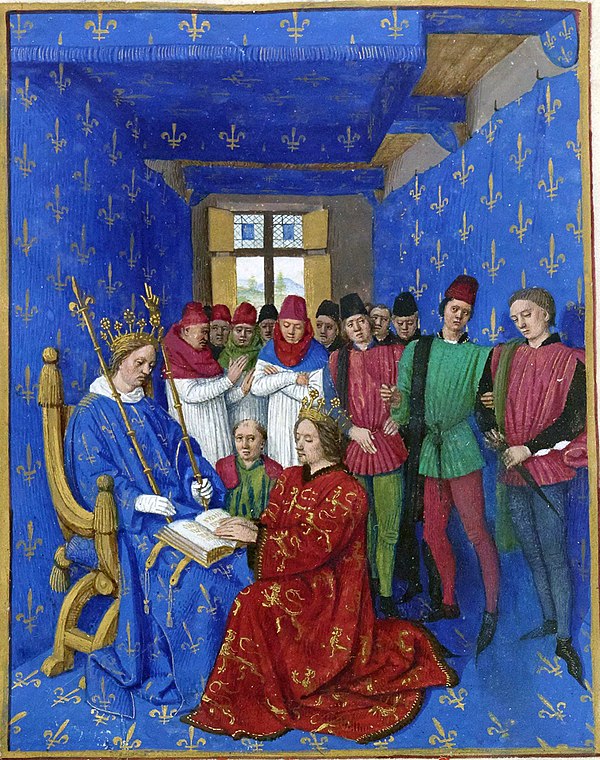

Early in 1304, Edward sent a raiding party into the borders, which put to flight the forces under Fraser and Wallace. With the country now under submission, all the leading Scots surrendered to Edward in February, except for Wallace, Fraser, and Soulis, who was in France. Terms of submission were negotiated on 9 February by John Comyn, who refused to surrender unconditionally, but asked that prisoners of both sides be released by ransom and that Edward agree there would be no reprisals or disinheritance of the Scots.

Excepting William Wallace and John de Soulis, it seemed that all would be forgiven after some of the more famous leaders were exiled from Scotland for various periods. Forfeited estates could be recovered by payment of fines levied in amounts deemed appropriate for each individual's betrayal. Inheritances would continue as they always had, allowing the landed nobility to pass on titles and properties as normal.

De Soulis remained abroad, refusing to surrender. Wallace was still at large in Scotland and, unlike all the nobles and bishops, refused to pay homage to Edward. Edward needed to make an example of someone, and, by refusing to capitulate and accept his country's occupation and annexation, Wallace became the unfortunate focus of Edward's hatred. He would be granted no peace unless he put himself utterly and absolutely under Edward's will. It was also decreed that James Stewart, de Soulis and Sir Ingram de Umfraville could not return until Wallace was given up, and Comyn, Alexander Lindsay, David Graham and Simon Fraser were to actively seek his capture.