History of Thailand

The Tai ethnic group migrated into mainland Southeast Asia over a period of centuries. The word Siam may have originated from Pali or Sanskrit श्याम or Mon ရာမည, probably the same root as Shan and Ahom. Xianluo was the Chinese name for Ayutthaya Kingdom, merged from Suphannaphum city state centered in modern-day Suphan Buri and Lavo city state centered in modern-day Lop Buri. To the Thai, the name has mostly been Mueang Thai.[1]

The country's designation as Siam by Westerners likely came from the Portuguese. Portuguese chronicles noted that the Borommatrailokkanat, king of the Ayutthaya Kingdom, sent an expedition to the Malacca Sultanate at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula in 1455. Following their conquest of Malacca in 1511, the Portuguese sent a diplomatic mission to Ayutthaya. A century later, on 15 August 1612, The Globe, an East India Company merchantman bearing a letter from King James I, arrived in "the Road of Syam".[2] "By the end of the 19th century, Siam had become so enshrined in geographical nomenclature that it was believed that by this name and no other would it continue to be known and styled."[3]

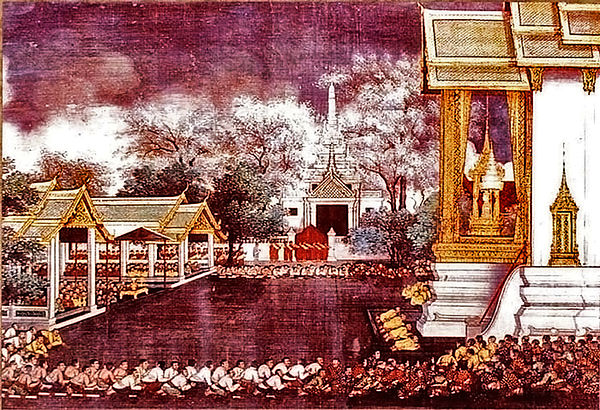

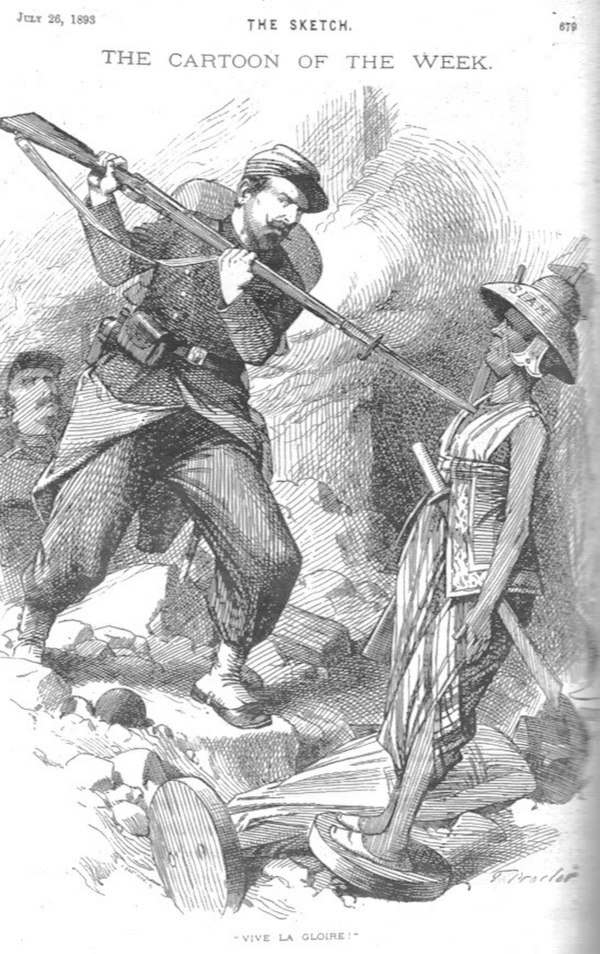

Indianised kingdoms such as the Mon, the Khmer Empire and Malay states of the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra ruled the region. The Thai established their states: Ngoenyang, the Sukhothai Kingdom, the Kingdom of Chiang Mai, Lan Na, and the Ayutthaya Kingdom. These states fought each other and were under constant threat from the Khmers, Burma and Vietnam. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, only Thailand survived European colonial threat in Southeast Asia due to centralising reforms enacted by King Chulalongkorn and because the French and the British decided it would be a neutral territory to avoid conflicts between their colonies. After the end of the absolute monarchy in 1932, Thailand endured sixty years of almost permanent military rule before the establishment of a democratically elected government.