The ancient kingdom of Iberia was located in what is now modern Eastern Georgia. Prominent from Classical Antiquity through the Early Middle Ages, Iberia played a significant role in the Caucasus region, fluctuating between periods of independence and subordination to larger empires such as the Sassanid and Roman empires. It was geographically positioned between Colchis to the west, Caucasian Albania to the east, and Armenia to the south.

The Iberians, ancestors to the contemporary Georgians, constituted the main ethnic group of this kingdom and were instrumental in the cultural and political development of the area. Over the centuries, Iberia was governed by various royal dynasties including the Pharnavazid, Artaxiad, Arsacid, and Chosroid. These dynasties later played a pivotal role in forming the unified medieval Kingdom of Georgia under the leadership of the Bagrationi dynasty.

The conversion of Iberia to Christianity, established as the state religion in the 4th century following the evangelistic efforts of Saint Nino and the subsequent endorsement by King Mirian III, marked a significant religious and cultural milestone. By the 6th century, Iberia's political landscape transformed as it became a province directly administered by the Sassanid Empire. This change culminated in 580 CE when the Persian king Hormizd IV abolished the Iberian monarchy after King Bakur III's death, appointing a marzpan to govern the region. The term "Caucasian Iberia" distinguishes this area from the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe.

Early History

The early inhabitants of Caucasian Iberia came from the Kura-Araxes culture. Among these were the Saspers, noted by Herodotus, who may have helped unify the local tribes. The Moschoi tribe migrated northeast, establishing the settlement of Mtskheta, which later became the capital of the Kingdom of Iberia. The leader in Mtskheta was known as mamasakhlisi.

First King of Iberia

Pharnavaz emerged as the first king of Iberia around 302 BCE, establishing the Pharnavazid dynasty after a significant power struggle. His reign marked the beginning of organized statecraft in the region. After repelling an invasion, Pharnavaz extended his control over much of western Georgia, including parts of Colchis (also known as Egrisi), and secured recognition from the Seleucid Empire in Syria. His administrative reforms included building the fortress of Armaztsikhe and a temple dedicated to the god Armazi, and introducing a new administrative division of the country into several counties called saeristavos. His successors maintained control over crucial mountain passes such as the Daryal Pass.

The era following Pharnavaz's reign was characterized by continuous warfare, with Iberia defending its territories from multiple invasions. By the 2nd century BCE, territories in southern Iberia that had been annexed from the Kingdom of Armenia were returned, and Colchian territories broke away to form independent princedoms. At the close of the 2nd century BCE, the Pharnavazid king Pharnajom was overthrown by his subjects after his conversion to Zoroastrianism. The crown was then passed to the Armenian prince Artaxias, who established the Artaxiad dynasty in Iberia in 93 BCE.

Under Roman rule

The strategic proximity of Iberia to Armenia and Pontus led to an invasion in 65 BCE by Roman General Pompey, who was at war with Mithradates VI of Pontus and Armenia. Despite this incursion, Rome did not establish permanent control over Iberia. In 36 BCE, the Romans returned, compelling King Pharnavaz II of Iberia to assist in their military campaign against Albania.

While the neighboring Georgian kingdom of Colchis was governed as a Roman province, Iberia chose to accept Roman imperial protection voluntarily. A notable stone inscription from Mtskheta indicates that Mihdrat I, ruling from 58 to 106 CE, was acknowledged as "the friend of the Caesars" and "the king of the Roman-loving Iberians." In 75 CE, Emperor Vespasian fortified the ancient site of Arzami in Mtskheta for the Iberian kings, illustrating continued Roman support.

During the reign of King Pharsman II from 116 to 132 CE, Iberia began to regain some of its earlier autonomy, despite strained relations with Emperor Hadrian, who attempted conciliation. It was under Hadrian's successor, Antoninus Pius, that relations significantly improved, leading to Pharsman's visit to Rome, where he was honored with a statue and given sacrificial rights. This era marked a shift in Iberia's political status, recognizing it as an ally of Rome, rather than a subject state, a status maintained even during Roman conflicts with the Parthians.

Religious practices in Iberia during the first centuries CE included the worship of Mithras and Zoroastrianism. Archaeological finds in places like Bori, Armazi, and Zguderi revealed silver drinking cups depicting horses at fire-altars, reflecting the syncretic nature of the Mithras cult, which integrated with local Georgian beliefs and possibly preceded the veneration of St. George in pagan Georgia. Over time, Iranian cultural influences deeply permeated Iberian society, as seen in the adoption of the Armazian script and language (based on Aramaic), Iranian-style court and elite dress, Iranian personal names, and the official cult of Armazi, established by King Pharnavaz in the 3rd century BCE.

Between Rome/Byzantium and Persia

The establishment of the Sasanian Empire in 224 CE by Ardashir I significantly altered the geopolitical landscape for Iberia, shifting its political orientation away from Rome towards the new, centralized Sasanian state. This transition occurred as the Sasanians replaced the less centralized Parthian Empire, bringing Iberia into their sphere of influence as a tributary state during the reign of Shapur I (241–272 CE).

Initially, relations between Iberia and the Sasanian Empire were cordial, with Iberia participating in Persian military campaigns against Rome. This cooperation is highlighted by the position of Iberian King Amazasp III (260–265 CE), who held a high rank within the Sasanian realm, indicating a partnership rather than subjugation by force. However, the Sasanians also demonstrated aggressive expansionist policies, notably through the promotion of Zoroastrianism in Iberia, likely established between the 260s and 290s CE. The religious shift marked a deeper Sasanian influence in Iberian cultural and spiritual life.

The situation evolved with the Peace of Nisibis in 298 CE, when the Roman Empire regained control over Caucasian Iberia, reestablishing it as a vassal state. This agreement also acknowledged Mirian III, marking the beginning of the Chosroid dynasty, as the king of Iberia, thereby reasserting Roman influence in the region while maintaining local dynastic continuity.

Sassanid Rule

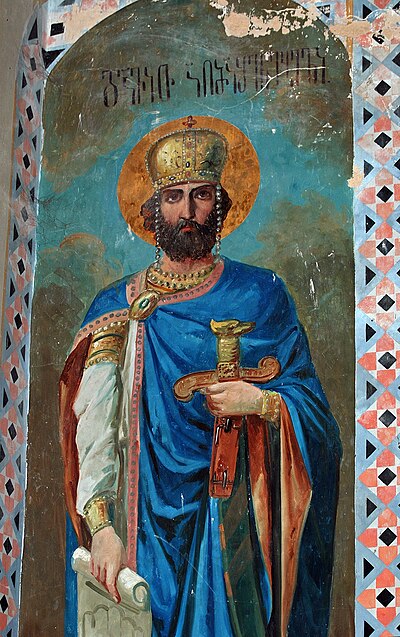

The religious landscape of Iberia was profoundly reshaped around 317 CE when King Mirian III, influenced by the missionary work of Saint Nino, a Cappadocian woman who had been preaching in Iberia since 303, converted to Eastern Orthodoxy along with his nobles. This conversion led to the declaration of Orthodoxy as the state religion, strengthening cultural and religious ties between Georgia and Rome (later Byzantium). This shift had a substantial impact on the state's culture and society, leading to the decline of Iranian artistic influences in Georgian art by the fourth century.

Despite these changes, the political situation remained tumultuous. After the death of Emperor Julian in 363 during his campaign in Persia, Rome ceded control of Iberia to Persia. Subsequently, King Varaz-Bakur I (Asphagur) (363–365) became a Persian vassal, a status formalized by the Peace of Acilisene in 387. However, Pharsman IV (406–409), a later ruler, managed to preserve a degree of autonomy for Kartli (Iberia), ceasing tribute payments to Persia.

The Sassanian rulers responded by appointing viceroys, or pitiaxae/bidaxae, to oversee Iberia, eventually making this position hereditary within the ruling house of Lower Kartli, thus creating the Kartli pitiaxate. This development strengthened Persian influence in the region, turning it into a hub for Persian cultural and political interests. During this period, the Sasanians challenged the Christian faith of the Georgians, promoting Zoroastrianism, which by the mid-5th century had become a second official religion alongside Eastern Orthodoxy in eastern Georgia.

The reign of King Vakhtang I, known as Gorgasali (447–502), marked a relative revival of the kingdom. Though formally a Persian vassal, he managed to secure the northern borders by subjugating local mountaineers and expanded his influence over western and southern Georgian territories. He established an autocephalic patriarchate at Mtskheta and moved his capital to Tbilisi. In 482, he initiated an uprising against Persian control, embarking on a prolonged and ultimately unsuccessful war for independence, which lacked Byzantine support and led to his death in battle in 502.

Fall of the kingdom

The rivalry between Byzantium and Sasanian Persia for dominance in the Caucasus led to significant political changes in Iberia. After an unsuccessful Georgian insurrection in 523 led by Gurgen, the region saw a reduction in the power of its kings, with Persian authority becoming more pronounced. This culminated in 580 when Hormizd IV, ruling from 578 to 590, abolished the Iberian monarchy following the death of King Bacurius III, transforming Iberia into a Persian province governed by a marzpan.

In response to these changes, Georgian nobles appealed to Byzantine Emperor Maurice in 582 to restore the Iberian kingdom. However, in 591, a compromise between Byzantium and Persia resulted in the division of Iberia, with Tbilisi falling under Persian control and Mtskheta under Byzantine oversight.

The fragile peace between Byzantium and Persia disintegrated at the start of the 7th century. Around 607, Iberian Prince Stephan I allied with Persia in a bid to reunite all Iberian territories, a goal he reportedly achieved. However, the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius launched a successful offensive against the Georgians and Persians in 627 and 628, reasserting Byzantine influence over both western and eastern Georgia. This dominance persisted until the Arab invasions of the Caucasus later in the century.

Under Arab Rule

The Arab conquest reached Iberia around 645 CE, significantly altering its political landscape. The local prince, Stephanoz II (ruling from 637 to around 650), was compelled to sever ties with Byzantium and acknowledge the Caliph as his overlord, transforming Iberia into a tributary state of the Arab Caliphate. By 653, an Arab emir had been installed in Tbilisi, further cementing Arab influence in the region.

As Arab control began to wane in the early 9th century, Ashot I (813–830) of the newly established Bagrationi dynasty, based in southwestern Georgia, capitalized on the weakening Arab rule. He consolidated his power, establishing himself as the hereditary prince of Iberia. His efforts laid the groundwork for the resurgence of local rule, leading to Adarnase IV of Iberia, who was still formally a vassal of Byzantium, being crowned as "king of Iberia" in 888. This revival of local sovereignty continued to progress, culminating with Bagrat III (ruling from 975–1014). Bagrat III successfully unified the various Georgian principalities, heralding the formation of a united Georgian monarchy that marked a new chapter in the region’s history.